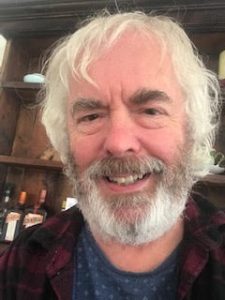

By Michael Cains.

I don’t think much about my grandfather these days. He died many years ago back in England, to where I have never returned. I remember him as a big man, with a big influence over his four children, and indirectly over me, one of his four grandchildren. That all but vanished when my father bundled us onto a plane to Australia at Heathrow to escape him, and a brother and sister he didn’t love. His adored younger sister was a different story, but she suffered a fatal stroke a few years after we departed, not living much past her thirtieth birthday. Long term use of The Pill caused it, my mother said.

Confused and excited, we flew with my parents as “ten-pound poms”. Myself and my two siblings, a shy sister close to my age, and a four-year-old brother, nine years younger, who needed oxygen on the bumpy DC9. This was in the days before jet engines halved the flight, and we incessantly droned through the Middle East to Dubai, onto what was then Ceylon, then touching down in our new home after enduring Darwin’s steamy heat. We were wearing overcoats.

We lived a few weeks with my father’s lost Aunt who had emigrated “down under” years before with her loud and boisterous husband, rearing a daughter and a son now grown up as “real” Australians—the first we met. We had noisy cousins but never got close and eventually drifted away from them, as we had done from England. My parents visited the UK Settlers Club only once, scoffing that it was full of “whinging poms”. They were happy settling in a land of buzzing flies that only disappeared at dusk when the mosquitos came out to savage my mother. We burnt red if we were outside longer than twenty minutes until the baptism by the relentlessly brighter Australian sun bronzed our pale white bodies. Our eyes squinted and we learned the salute, and that dirge of a pledge recited at school assembly which was apparently required to remind the colonials they were part of a faded empire.

The man we called Grandad was a consistent letter writer and we devoured his neatly written words written on folded blue aerograms, sliding out the five-pound note that always came with them. I cannot remember the words today as I never kept any of his letters. The money flitted away but we always knew the exchange rate. He was becoming part of a distant past in an old world we had left behind while we were busy growing up in the 60’s in a new one, about to get older.

I remembered him as a big round man in a blue police uniform. He had retired when we were still young in England but couldn’t give away being a Chief Superintendent, so he became a police reservist, serving warrants to keep his authority intact. We went with him sometimes in the immaculate green Morris Minor he drove like a police car, nearly airborne over jumps on English country roads. He ruled the family, watching carefully over his grandchildren, regularly taking us to a park called Ashridge which we all loved, riding donkeys. My sister had stayed with them whenever she could as they adored her. I was the one they had big expectations for, bespectacled and bookish. They saw me as being the first in the family to go to university, and the uncle married to my Dad’s cherished younger sister promised to pay for my fees at Oxford or Cambridge. But we left before then.

As his memory faded from ours, my grandfather’s letters arrived less frequently. My sister and I moved out of our parents’ eastern suburbs home, got married and he became still more remote. We all seemed to do that too easily. My father was happier away from his influence and he abandoned a lifetime of employment in the automotive industry requiring him to travel two hours to Holdens in Fisherman’s Bend, content working in a local chocolate factory. He eventually got my brother a job there, but that’s a story for another time. I failed my matriculation exam, but went on to attend university at twenty-five, courtesy of Gough Whitlam’s free education and the Mature Age Entry scheme. My Grandad was never to know that I did become the first in our family to graduate with a degree.

The grandfather I knew so little about flew to Australia for a brief visit. He came to see my father and his older sister, her husband and a cousin we had little time for, who had also emigrated a few years later, perhaps attracted by the rare answers we made to our grandfather’s letters. My parents didn’t like her and she drank too much. I saw my grandfather with my Nana, before she slipped into dementia, at my aunt’s place not far from my parents. We spent a few hours talking like strangers with little in common. I wasn’t the twelve-year-old boy he had said goodbye to in London twelve years before, and I didn’t know who this man was, although he was not a big as I remembered him. We didn’t even have a family get together such were the feelings between my father and his two surviving siblings, I suspect.

Although not privy to conversations between my father and my grandfather, it was not long after the latter’s visit that my father became the State Secretary of the Confectioners Union, elevating him and my mother’s social standing, lifestyle and exposure. It was not to last, thanks to the vagaries of Australian union politics, and he returned to driving a forklift at MacRobertsons Chocolates, now absorbed by the global Cadburys. They still made Cherry Ripes, but Dad actually hated chocolate.

Life went on and we raised up families, survived divorces, and heard remotely of distant deaths in far-away places. My Grandfather was one of these and my father flew back for the funeral. He didn’t talk much about it except to say that his mother’s dementia had been long hidden by his father. Small families vanish, and the close ties never made are looked back on with resignation, or as lost opportunity.

My father rarely talked about his father, as I rarely talk about mine. Becoming older I reached the conclusion that our family doesn’t do much talking, unless there is something important to say. They avoid each other, spreading like an oil-slick on an English duck pond in a scramble to put distance between themselves. The flight from England was only the first part of this, and I never lived close, or got close, to my sister, and especially my brother. He died a lonely alcoholic after divorcing his wife and four children. I have tried to write about this but succeeded only in writing a poem about which I still spill a tear when I read it aloud. My parents moved away to Tweed Heads after their retirement, and my mother still lives there twenty-two years later.

Before he died my Grandad sent me his police pocket watch and a button from his uniform tunic, but my sister has them. She keeps things more carefully than me, appreciating their sentimental value far more than I. In her family tree research she found a newspaper clipping with a photograph of Prince Philip visiting Luton in the 1950’s, walking and talking with the Mayor clinging onto his arm. There, on the Prince’s other side, was a large figure in a police greatcoat, all alertness and attention, watching the crowd on a cold winters day.

That photo brought home to me how little I remembered of the larger than life figure who was one time the centre of our small family. It made me both proud and sad. Pride in knowing this man was a pillar in society, a high-ranking uniformed policeman in one of the world’s best police forces. Sadness because I allowed life to get in the way of really knowing him, of never letting me return to visit, or staying more in touch with a remarkable man. You can blame life, or distance, but that would be a mistake. The regret is all mine, so I tuck it away as one of the things I don’t think about. My grandfather.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael escaped regular employment two years ago, and when not renovating or travelling anywhere with his wife in their Avan campervan, he writes. He never really stopped this since school, receiving frowns for his creative responses to staid organisational communication before finding a niche as a part-time motorsport journalist for fifteen years. He leans towards Speculative Fiction, but will try anything, rediscovering a latent love of poetry and short stories. A novel or three are in progress.

Leave a Reply