By Kat Skarbek

Black Country England in the 1960s was anything but swinging. It was a place of dirt and hard labour and sweat. The streets were full of terraced houses, knitted together in red brick rows, pulsing with the kind of decaying urban life that people tried desperately to get away from. Gangs of snotty kids filled the streets with swearing, threats and homemade go-carts created from things pulled out of ponds, or pilfered from each other’s houses. The pubs filled to overflowing with working men still black from mining, spilling shining slag from boots and trousers as they tramped through the bar.

The only revolution here was industrial. Music, sing-a-longs only, was ground out in those same bars, on out-of-tune pianos and nobody gave that shite off Top of the Pops, with poofs poncing about with big hair, a second sneering glance. Everyone said those shirt lifters were just asking for a good kicking. So my sister and I listened to our poncy music in secret on scratchy radios, when Dad was down the pub and before the evening punch up inevitably started. We so loved to escape into The Rolling Stones and The Beatles but though we could carry a tune well enough, none of us were musical in the least, especially her. Which is why what came next was so odd.

She couldn’t play the piano, my older sister. Not during the day at least. I don’t mean that anyone stopped her, I mean she wasn’t capable. She had never had so much as a lesson on an ordinary piano, let alone the kind of specialist tuition it would take to play the gigantic church organ jammed, like a clergyman in a priest hole, into our dilapidated shed. She couldn’t even read music—none of us could. Some of us couldn’t read at all, including our dad. And how that thing ever got into the shed I will never know. We all knew better than to ask where anything came from. Questions of that nature usually resulted in a swift smack across the back of the head.

The shed itself was pressed aggressively up against next door’s fence, swollen with things my dad had ‘acquired’ but never sold because he was a consummate hoarder. It was a disorder he passed on to our oldest brother, which would, years later, lead to his wife leaving him after 40 years of marriage. It was also home to any animals we could get away with hiding from Dad. My sister’s white mice, who bred wantonly and who were slowly but surely being sacrificed to my brother’s kestrel. My tiny crumpled box of three- week-old kittens, their mangy mother being fed with any greasy scraps I could liberate from the frying pan lard in the kitchen. I would toss bits to her as she slunk across our overgrown lawn, avoiding contact. Turns out she was right to be wary. Dad eventually found the kittens and drowned them all in a bucket.

So when we began to be awoken almost nightly by eerie music sliding up to our cracked bedroom window and sneaking inside with the threat of trouble, we acted fast. Whoever woke first would dart downstairs, heart pounding, nerves strained, trying to be both quiet and quick, to race up the garden after her. We knew we had to close the lid of the organ, quiet the barking dog, and walk our somnambulistic sister back upstairs to bed. Without being heard. Without being seen. Without waking up the snoring drunk in the room next door.

The unsettling night symphonies seemed to happen most when things were really bad at home. After the fists and the crying had stopped downstairs and we had fallen into an uneasy sleep curled around each other, my sister’s body would walk itself out of the wet sheets of her single bed and out of the back door of our cold brick house. She would walk barefoot, insensible to the dog shit, broken glass and old car parts that littered her path. Down past the kennel where our growling white boxer, Spike, the scourge of the coal, post and bin men, was chained, and sightlessly find her way to the dank dusty shed.

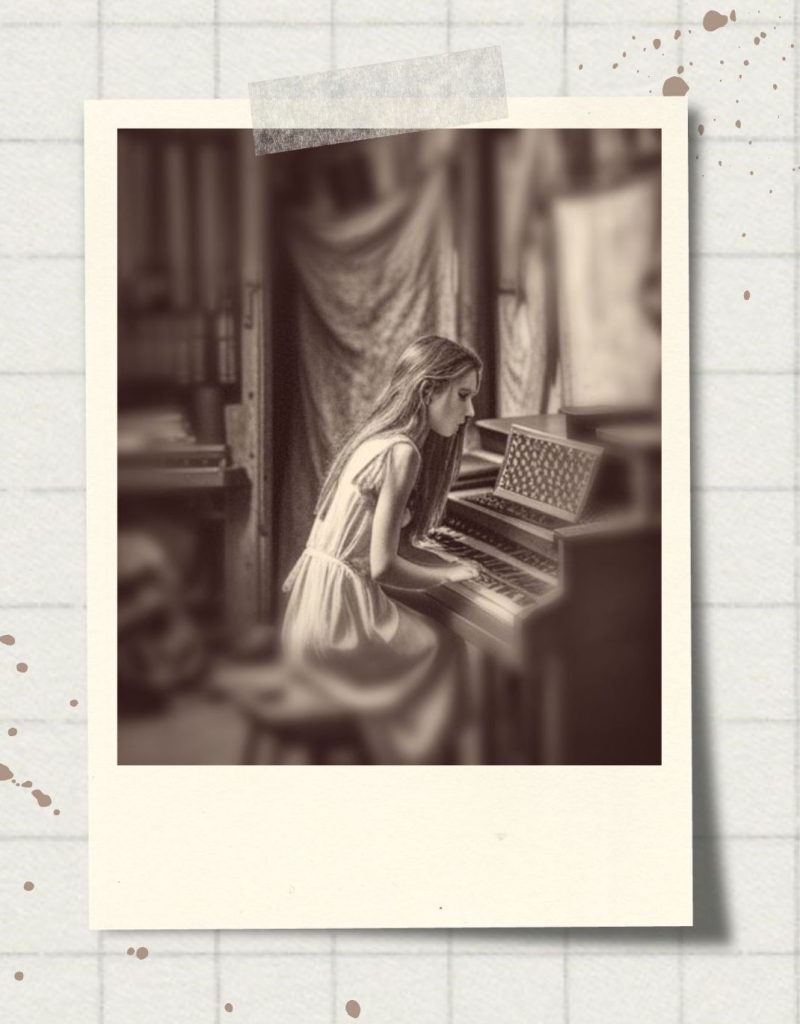

We would find her hunched in the dark, a tiny white bird dwarfed by the oppressive hulk of the organ overflowing the back part of the shed. Eyes open but unseeing, her fingers conjuring slow judgemental music best left for Sundays. No one knew why it was hymns she played; we weren’t religious and certainly God had no place in our house, but nonetheless that is all she played. Her audience the night and the fat garden spiders that watched from the roof.

Sometimes it would be mum who would get to her first. When the pills she took to avoid my dad’s drunken advances hadn’t worked or were overpowered by anxiety, she would slip out of their bedroom and whisper frantic instructions in the dark as she threw a towel over the wet patch and helped us lay my sister back down and cover her up. She needn’t have said anything. We all knew the drill. We all knew what it would cost us, what it would cost her, if Dad woke up. She couldn’t even change the bed or my sister’s nightclothes. She had to wait until my dad had gone to work before she stripped my sister’s bed, and washed and dried everything before he came home and demanded the curtains closed, his dinner on the table and the absolute silence needed for him to eat and watch the news on TV.

Mum, already stretched thin from a life that seemed designed to knock her down and trample her where she fell, tried everything she could think of to stop my sister from sleepwalking and playing that organ. She tried warm milk and honey to aid sleep. She harvested stalks of lavender and chamomile flowers from my granny’s back garden and put them in tiny cotton bags sewn from rags bought from a jumble sale and placed under her pillow. She even tried slipping my sister a little whiskey before bed, hoping that the tiny nip would create a more sluggish sleep and prevent the night wanderings. When all of that failed, she begged my dad to get rid of it. She knew there were people who would buy it and God knows we could have used the money. But he owned it and once he owned something, it was his. On the terrible nights he was awoken from his beer sodden slumber, his Black Country rage was quick and vicious.

‘She ay bloody sleepwalking, hers down there with a chap, ay her! If hers letting someone have her, I’ll kill ‘im and then I’ll break her bloody neck!’ The words simmered with rage, the spite coming off him in waves. Our bodies were frozen, rigid with tension and ready for flight, danger a tang of copper in the air.

‘Yow’m’all bloody useless. Yow ay got the brains yow was born with. If I find out hers got a chap in there, I’ll bloody kill yuhs all!’

The last was always aimed at my mother and there were definitely nights it seemed a likely outcome. Then he was away to the shed and my sister was hauled back into the house by the scruff of her nightie. Her eyes wide and showing too much white, knuckles blooming with purple.

Apart from when she was found by my dad, she couldn’t remember anything of her night-time jaunts into the garden. The first few times we asked, we were incredulous. How could she not remember something so astonishing? So odd? Slowly, we stopped asking questions, afraid of the sharp feral look that would come into her eyes, or worse, the wounded look, as if we were all playing some horrible trick on her to amuse ourselves. I think she knew though, deep down, that we would never do that. The risk of consequences was always too high. We just accepted our roles as night guides and protectors, the way she accepted those same roles in the schoolyard. We looked out for each as best we could.

I would sometimes catch her in the late afternoon, sitting on the broken upturned crate that passed for a stool, fingers softly wandering up and down the large keys, a look of gentle puzzlement on her face. Or listening intently to the differences that this knob or that lever or one of the pedals made to the key sounds. I asked her then, when the boys were out of earshot, when we could talk without the quick fear that passed over our youngest brother’s face when we spoke about things that could get us into trouble, why she thought it happened. Her face would cloud over and she would say, ‘I dunno. Mom ses maybe I could play the piano in another life and when I’m asleep, the part of me that lived before takes over and remembers.’ Then she would fall silent again.

I liked the idea of a different self, living a different life, taking over and living for a few brief night darkened hours through the translucent hands of my big sister. Hands that would, in the not- too-distant future, get her expelled from school for punching a teacher. Hands that could, if she was feeling mean, make you really pay. The near nightly organ playing went on until the evening when the police finally came to the door and arrested my dad. Mum, post hospital, was told in no uncertain terms that we would be taken into care, separated from both her and each other, if she didn’t shift her loyalties from him to us.

That night we were all awoken by my sister playing something only my mother recognised: ‘Saul’s Funeral March’. Though we crept downstairs one after another, none of us was brave enough to enter the shed and remove her hands from the icy keys until the last notes had sounded. We left the next day with the clothes on our backs and some money mum had sewn into the hems of our coats. Though my sister continued to wet the bed for a little while longer, she never played anything again. Asleep or awake.

Decades later Dad died alone on the floor of that same narrow, dirty kitchen we had all walked through to get to the shed. The lonely victim of both a stroke and a catastrophic heart attack. He lay undiscovered for many days. When the time came to clear the property of his years of hoarded belongings, none of us wanted anything from that house, especially not the organ—which once would have been worth a few bob but was now festering, rusted and riddled with damp and woodworm and almost one with the remains of the shed that surrounded it. On some level, the organ had served us a warning and precipitated our final exit from that rancid little house, but it all felt tainted with the misery we had lived with for all those years. And we were all a little superstitious about bringing things soaked in so much unhappiness into our homes, to touch the lives of the people we loved.

Our belongings were still in the rooms we once shared, which had been kept just the way they had always been, as if Dad had expected us back at any moment. My dirty white teddy with the purple button eyes still sat stiffly on my bed waiting for me. My younger brother’s broken dartboard still stuck to the wardrobe door. Everything seemed to shine with a patina of misery, especially the photos of us all together. In the end though, I did take something. Something small slipped into a dress pocket when the others weren’t looking. One blurry black and white photograph, tea stained at the edges, creased and yellowing, taken during the day, of my sister sitting at the organ, her head tilted towards the keys, over which her long spidery fingers were splayed, wearing a rare, if somewhat puzzled, smile on her face.

About the author:

Kat Skarbek is a writer of both fiction and non-fiction. Despite her precocious beginnings as a 10-year-old playwright (over-confidently putting on a ghostly school play that she wrote, directed and acted in), her most recent leanings have been toward short stories with folk horror leanings and, creative non-fiction. She is currently incubating an idea for a novel of historical fantasy fiction which, frankly, terrifies the bejesus out of her, so that’s got to be a good sign.

Kat likes to think of herself as a bibliophile but her husband says she can call it any fancy name she wants, it’s basically book hoarding, and where the hell is he going to find space for them all anyway? Although she is an ‘all genres’ type of gal, at the moment she is devouring mythological and fairy-tale retellings from such authors Natalie Haynes and Angela Carter and genuinely unnerving horror from the terrifying minds of Adam Neville and T. Kingfisher.

Aside from writing and being the mother of a brace of character-building teenagers, she spends her time teaching women how to make their midlife the most fulfilling and inspiring part of life so far.

Kat is very chatty in person but then feels guilty about talking too much. She is a restless nomad in love with family travel, gin, swearing and knitting, though not necessarily in that order.

Leave a Reply