Small Town Secrets, by Jo Curtain

![]()

NEVER DISPLEASE AN ANGRY MOON

JULIE RYSDALE

Stercesn-Wotllams, a pleasant village that clung to the edge of a deep emerald loch and receded to the foothills beneath an imposing escarpment. The surrounds of the village were hailed by locals as places of wise solitude and thoughtful silence. Others would say it was a regressive town, even backward … but that lay in the eye of the beholder.

M had lived in the village all his life. His prowess as a dry-stone waller, long celebrated. But gossips whispered, ‘There’s more to that cagy M than his harmony with stone … mark my words!’ Rumour was that M, and M alone, knew the meaning of Stercesn-Wotllams and its cryptic significance. But M kept mum. He was oft encouraged to share an ale or two, but always refused: maintaining a secret required steady sobriety, and stone walling, a steady hand.

M’s energy started to fade and fail and his hands gnarled and knotted. He knew his time was brief. When his great, great, great, grandfather accepted the role of Village Stonewaller long ago, during the time of The Dark Mystery, he agreed to stymie any discovery of the village name’s meaning. M had reluctantly inherited the role. Barren and childless he had no heir for this undesirable responsibility. All he could wish for was the celestial signal that it was time for the Grand Revelation.

His back hunched, M discreetly left his stony cottage at the end of the lane, as he had done each evening since his father’s passing. The overgrown lane tumbled with brambles and honeysuckle cloaking his shady movements. Swathed in darkness, with the cloying floral scent his only companion, he searched the sky, eternally hoping for the sign to unleash the mystery.

Many moons had waxed and waned, but each night the hushed heavens offered nothing … until now.

‘Look ye now!’ He exulted. Towering above, an angry blood moon glowered. As he cheered, it whipped the wind to harass the trees and sent the frightened grasses quivering. And, there! Hush and hark! At long last! The tinkle of bluebells rang out the ancient Celtic reel he had awaited! Barely perceptible at first, then M could feel the rhythm! His bunioned feet boogied! It was time!

With haste and an ale, he began the task of secreting snippets of words and letters within his legendary stone walls: tucking a part letter here, a word there. Would the pieces be plucked from where purposefully placed? That was his plan.

Sapped and soused with ale and joy, whole words were stuffed carelessly between cracks. Sometimes befuddled, ‘hamlet’ was scrawled on a stub and wiggled beside a stone. Sometimes, ‘small’ became ‘little’, sometimes ‘secrets’ smudged to ‘hush-hush’. What did it matter! Satisfied, he stumbled home …

Aghast, the mortified livid blood moon tripped and whipped a turmoil. The reel became a jig and the agitated wind sneezed, flinging letters and words soaring o’er the escarpment.

A scrabble of words playfully teased and wafted, fluttering to the loch’s eager waves.

![]()

SUITCASE

JAN PRICE

muffle it down from its waiting

place it on carpet out of sight

of the door-squint.

Don’t snap the locks turn the key true

then thumb and finger the fastenings

control each spring

slow-lifting the catches.

Watch the mothballs don’t rumble

over dints like night skaters

over cracked paths on quiet back streets

waking light sleepers.

From a camouflaged corner

velvet-draw the purse recount the train

the taxi the hotel and again the train.

Pack only warmth for the summer

may be an illusive season.

Between cashmere and cotton cushions

whisper hello to mother’s framed sad eyes;

slip into the coat lining a Moulin Rouge

lipstick. Now

with coat over case and hand beneath

press down count ten don’t breathe easy

click-close the locks again.

Leave dependence in dust under the bed

exhume laughter throw away its wreath

and as dawn struggles under weight

of winter take hold of the handle

it will be lighter than imagined

then leave

by the front door.

![]()

SMALL TOWN SECRETS

JO CURTAIN

There are flowers you haven’t even seen. Nora Bloom was the daughter of a florist. Her childhood was filled with seeds and flower cuttings, books in which to place her favourite flowers to dry. Nora not only inherited her mother’s singular passion for all things botanical but her shop. An enchanting place filled with the most exquisite displays of colours and scents at the centre of a small town.

Nora locks up the shop for the night. She carries a bunch of peachy dahlias. The street is as quiet as a museum. It glows with posters of smiling faces, backlit with soft, calming lights. Dreamy and spotless. Nobody really takes the time to look. Beyond their shiny white teeth and luminous cheeks is a universe radiating subliminal messages subverting reality.

She is meeting Norman at the Fat Cat restaurant. He wants to show her his invention. Norman uncuffed, and his tie loosened. He is an advertising man. He is also exquisite and oh-so-smooth. He looks up, ‘It’s just a prototype.’ The tablet stands up like a vase. Twelve red roses.

‘I see,’ she says, looking at the image and then down at the bunch of dahlias, unimpressed.

‘I thought you could market it to hospitals. No mess.’

‘Umm, fragrances released through your device have already been invented,’ I say.

Leaning towards her, ‘Yes, but not like this,’ bringing the device towards her, ‘none capture the nuance of a fragrance like I have.’

He was right. It was unlike the flat, homogenous fragrances created. It was sublime with whiffs of musky, myrrh-y, clove-ish wood and dabs of citrus.

The waiter set their meals on the table. They eat in silence. Nora considers – a whole new market in sustainable floristry – no more packaging, delivery or leftover stems. Devilishly clever, she hardly knows what to say.

*

Walking home, a lone woman blocks their path. She is crying. Nora cannot remember the last time she saw a person publicly crying. Their small-town streets, slick and clean, quickly dispense with such messy displays.

The woman looks at them, ‘Do you have a moment?’

Norman looks awkwardly at his feet. Nora stutters, ‘No, we’re in a rush, you see …’

The woman’s brow crumbles, and Nora quickly shoves the dahlias towards her, ‘Here, take these.’ Without another look, they walk away.

Later. ‘I wonder who she is?’ Norman rubs her shoulder, ‘Don’t worry, she’ll be all right.’

Shamefully, Nora hides her thoughts of wanting to report the woman.

*

Late afternoon is interrupted by a news report. A kilometre-long trail of peachy-coloured dahlia petals has been found along Consolation Bay. Curious walkers followed the petals, and when they came to the last, they found the body of Henrietta Bloom.

The next day, the authorities collect the petals, and Henrietta’s death is wiped clean from public memory. But for Nora, it is like the stain of lily pollen. It remains, but you’re not quite sure what it is you’re seeing.

*

Norman embraces her longer than usual, and she wakes to red roses.

![]()

THE BAKED BAKER

ALLAN BARDEN

In 1958 John Flynn, an Irishman, was employed as a baker in a small Tasmanian town. John worked the nightshift starting at 7.30pm where his first job was to clean up the bakery after the day’s activities. When he finished cleaning John would sleep on an onsite stretcher until 3am when he would wake to fire up the ovens and prepare the bakery for the ensuing day’s trade.

John’s boss, Harold Pinter, would arrive at the bakery at 5am to start baking and John would go home for a few hours before returning later to undertake bread delivery to the townsfolk. In 1950s Tasmania it was common for small towns to have bread delivered by the town bakery.

John was a good looking polite young man and popular with the customers on his daily bread delivery run. Most of the customers on his run were women because their menfolk were at work. Many found his Irish accent attractive.

Rumours had John engaging in a number of affairs with various ladies in the town. Indeed, there had been several threats and accusations levelled at him by suspicious husbands and boyfriends on his alleged amorous daytime activities, but he was never caught in a compromising act.

One winter’s morning when Harold Pinter arrived at the bakery to bake the day’s bread, he noticed that John had not left the door key out for him. Harold knocked on the door several times with no response. As he had no other way of entering, Harold had to break the door to gain entry. Once inside he saw that the cleaning had been done but the lights were on. There was no sign of John.

A cooking smell and a sizzling sound directed Harold to the slightly ajar door of the oven. Harold stooped to take a closer look and saw a hand with five charred fingers. He realised he was looking at the charred parts of a human body. Panic stricken he rushed away to get the local police sergeant.

The sergeant and local ambulance officers identified the charred body as that of John Flynn.

How John ended up in the oven has never been determined. Was it suicide? Did he accidentally crawl into the oven to keep warm while in a drunken state – he liked a Guinness or two. Was he murdered by a jealous husband or boyfriend; a prevailing thought of many townsfolk? The police investigation could not determine a likely suspect although, if rumours were true, a possible motive existed.

At John’s funeral it was obvious that he was highly regarded, especially by the many local womenfolk who attended – some quite distressed. Clearly John’s customer service and attention to their needs on his daily bread delivery rounds would be missed.

The reasons for John Flynn’s demise remains unknown and for some or someone in the town, a secret to this day.

![]()

THAT THIN BLUE LINE

SUSAN TATTERSALL

It’s a small town, the place I inhabit.

Capitalised on a solid impenetrable wall and underlined for emphasis.

The underlining strikes me blue, a thin blue line.

The words a simple reminder of how small my world has become since I let you all back in.

I opened the door one day.

I opened the door and you came rushing in.

I opened the door one day and the brick wall collapsed.

The poker face shattered, leaving all those secretly held memories to contend with.

My wall no longer impenetrable.

My secrets no longer secret to me.

My filing cabinet open and my world so much smaller.

I’d been holding you all tightly.

My small town secrets.

Neither friend nor foe, you’d buried deeply

with nowhere to go.

I’d been holding you all so tightly without knowing who you were.

Pushed down to the custodians of survival

for so many years.

Unconsciously designed to keep me and mine safe.

You’re a better part of me now in the knowing.

My small town secrets.

Underlined for emphasis in that mocking thin blue line.

Yet still not friend nor foe.

Simply memories and feelings now clamouring for attention and escape.

Finally, greedily vying for healing.

A welcome explanation for holding so much my dear.

It’s a small town with secrets, the place I inhabit.

Capitalised on a solid impenetrable wall and underlined for emphasis.

A flashing neon sign haunting my sleep.

Memories and fears reducing my waking world.

Safety switches still on, mocking, chastising and isolating.

Screaming how could I have been so unaware.

And anger at the job that didn’t care.

The underlining strikes me blue, a thin blue line.

Above, what you see in times of need, or as responses to ill deeds.

Below, the scenes, the sounds, the smells. The tellings of lives changed indelibly signed and filed.

The words a simple reminder of how small my secret world has become since I let you all back in.

I opened the door one day.

I opened the door and you all came rushing in under the mask of the thin blue line.

My small town secrets are no longer the secrets held to keep me and others safe.

Pieces of brick wall and shattered poker face, symbols of promise and healing.

A belated invitation of redesign and rebuilding

![]()

THE GREEN, GREEN GRASS OF HOME

GEOFFREY GASKILL

I was born and grew up in a small town. My greatest fear was I’d die there.

During my childhood, everyone in the place agreed with my Uncle Tony when he said, ’Small towns are the best places for kids to grow up in.’ During our endless, hot and boring summers, we begged to disagree, even as we dared not say so.

Only when I grew older was I prepared to ask, ‘What’s wrong with other, bigger places?’

‘No-one knows you,’ Uncle Tony told me. ‘You’re just a brick in a wall.’

As far as I was concerned, the difference between my town and elsewhere, came down to the size of the wall, the bricks and the cement holding them together.

I came to recognise our town was like the Bible with its all those thou shalt nots.

‘What about the thou shalt’s?’ I demanded.

‘That’s just the way things are,’ I was told and given a clip over the ear for my trouble.

In my last Santa letter, I begged for a new home. ‘Anywhere else,’ I wrote. What that meant was greener grass, bigger bricks and better cement.

My brother Jed told me I was a dope believing in Santa. ‘You probably believe Uncle Tony as well. If you want out, you’ve got to do it yourself.’

The trouble with hearing something, is that you can’t unhear it. I became restive, the place intolerable.

I’d never noticed the town’s underbelly before. I wondered why my parents or Uncle Tony didn’t. ‘It’s just the Robinson’s–or whoever’s–affair,’ they’d tell me. I didn’t know what that meant. The harder I tried, the more confusing the world became.

‘Like everywhere else is perfect?’ my friend Mouse asked. I wanted to get out as much as he didn’t. ‘You’re such a dork.’

That made two people who thought I wasn’t all that bright.

Maybe I wasn’t.

It’s only when I left to go to university and search for that greener grass and those bigger bricks that I saw home for what it was. Of all the kids like me who left, none went back. When Uncle Tony wrote to me, he’d end each letter with, ‘When are you coming home to the best place in the world?’

Home.

I wanted to tell him I’d rather die than go back. ‘One day,’ I’d lie. ‘But for the moment, my job … I’m concentrating on getting a foot in the door.’ Later that turned into, ‘They’re so swamped at work right now I can’t just leave them in the lurch.’

In the end Tony, stopped asking.

The lies that came so easily to me, were the only certainties I’d brought from home.

Escapee mates of mine wrote similar lies in their letters.

One day … became code for never.

Mouse and Jed were right. I was a dope, a dork. The trouble was, I had become a dishonest one.

![]()

SMALL TOWN SECRETS

CLAUDIA COLLINS

The Cat Pounces:

The band took a break. June’s feet were hurting and her husband had vanished. No need to guess where he’s gone. Finishing her third glass of wine, she headed outside in the direction of the brick toilet block. She was about to flush when she heard the girls enter. Remaining where she was, June listened to their happy conversation.

‘Mouse, you’ve smudged your mascara. I’ll do your eyes again for you, if you like,’ Bronwyn offered.

‘Tim is such a spunk,’ sighed Angela. ‘Hey Mouse, what do you think of my brother? I saw you dancing with Joey a couple of times.’

‘You know she likes Bobby. Pass me your lipstick, Angela.’

‘There’s ‘like’ and there’s ‘loove’. Hurry up with my lippie, I want to go back inside before Tim finds someone else to dance with.’

The door creaked as it was opened and closed.

‘Well, what do you think of Joey?’ Bronwyn demanded the minute the door was shut.

‘He’s quite nice looking but … Why do you think Bobby didn’t ask me to dance?’

‘I thought he would have by now. Everyone knows he likes you.’

Mouse. What a childish nickname, June thought. She disliked the girl. The dislike was mutual. Obviously, she resents me marrying her father. I don’t know why, I’ve tried to be civil to her. She flushed the toilet and left the cubicle.

‘Bronwyn, you can leave now,’ June said as she washed her hands. ‘I wish to speak to Hilary alone. Family business.’

Bronwyn glanced at Mouse before bowing to a higher authority.

‘You are sixteen now, old enough to be told the truth,’ June said with her cat-like smile. ‘You can never be Bobby’s girlfriend. He is your half-brother. Surely you can see the resemblance? If Bobby didn’t ask you to dance, it’s probably because he is aware of the relationship.’

The Mouse Runs:

I bolted down the street, crying. The heel on my left shoe snapped. I kicked it off, and the right shoe as well. With every step I could hear my stepmother’s cruel words.

‘Bobby is your half-brother. Surely you can see the resemblance?’

‘There’s no proof,’ a tiny voice inside my brain made itself heard. I needed to know. There was little chance of being seen—most of the town was at the dance. I turned off the main road. A sharp stone cut my foot and I limped past the footy oval and up Bobby’s gravel driveway. I heard a car start, the familiar sound of my father’s V8. I hid behind a tree as the car’s headlights swept across the yard in my direction. Why didn’t Bobby tell me?

The tail lights receded into the distance and I hobbled back down the driveway. Tears ran down my face. I rubbed my nose with the back of my hand. How could I not have known?

There are very few secrets in a small country town. Somebody always knew, and someone always told … eventually.

![]()

EVERYONE KNOWS

GISELLE SIM

Here I stay in the out realms

Forever strangled in its arms

Never am I allowed to leave

I watch people come and go

They come in joy for change

They leave when joy is gone

The town holds secrets everyone knows

Secrets that cannot be spoken

Secrets only shown

I don’t get to leave

For I am a secret

That secret must not be known

A past that is present into the future

In a place that wants me dead

Imprisoned I serve the sentence for knowing

![]()

OLD SECRET

MICHAEL CAINS

Wind clattered loose timber against the weatherboard shop. Debris and grime piled up against the door, and the same wind blew dust along the abandoned street. An evil silence infiltrated and anything living gave the place a wide birth. An old car rusted onto the roadway where it had died long ago.

I inhaled a stench that was like old books soaked in urine seeping from buildings losing their struggle to stay upright. Dark clouds encroached; a hot wind rattled dead leaves into crevices. The sad little town radiated menace, and over my shoulder the murderous sound of crows echoed in the distance.

The address in my tattered notebook said Number Twenty. Wiping the glass door only smeared the grime but I could make out bare floors and overturned furniture. A sign leaning against the back wall surrendered to my squinting – HR Wells, Solicitors and Land Agents. This was the right place, but I severely doubted I would find anything yielding what I was looking for.

The door wouldn’t budge. I didn’t want to walk around the back so I fetched a crowbar from my car, levering the lock with an effort and a noisy splintering which reverberated down the empty street. I stopped, but nothing stirred.

Once inside I found furniture had been strewn around years before by somebody probably looking for the same thing. I slowly and patiently examined the wreckage by torchlight in the gathering darkness. Drawers and cupboards had been smashed open and ripped apart, more in rage than in search. In their haste maybe they had missed something. Maybe.

I crouched in the litter to look under the carnage, imagining a glint. Wait – it was! A tiny glimmer in the bright LED light. Shifting a collapsed chair I groped around under a fallen wooden filing cabinet, disturbing mildewed papers lying where they had been scattered.

‘Yes!’ My hand clasped around a tarnished signet ring. Lying there all these years just waiting to be discovered by someone who valued its secret. I turned it over in my palm, furtively looking towards the broken door, imagining a passing shadow. I rubbed dull metal of the ring behind a duller stone: Love TL. Thelma Littlejohn. Another of her secrets handed down through the years was finally revealed.

Closing the door to the shop as best I could I ran to my car clasping the ring and crowbar. Starting the engine I checked the rear-view mirror out of habit. That’s when I saw the huge four-wheel drive hidden under a scrawny gumtree a scant two hundred yards away. I moved off slowly, and it followed, not turning on lights in the gathering dimness of dusk.

Accelerated rapidly I narrowly avoided the rusted wreck to drive quickly out of the country town. The black four-wheel drive easily stayed behind my electric car; it was in no hurry but was definitely after the same secret. I drove into the gloom, my eyes straining, teeth clenched.

![]()

COPY THE RIGHT OWNER

JOHN HERITAGE

![]()

MYSTERY MAN

CATHERINE BELL

The woman waits by the window each morning. Tap, tap, tapping her feet. At first, she is slightly intrigued. But when her fascination turns to obsession, she is unable to start the day until he passes by.

The battered white ute comes into view and putters slowly past, like an old man on borrowed time. It glides to a stop near her house. She is curious. It’s a residential street and not where beachgoers normally park.

A thin, middle-aged man alights. A brown Kelpie yaps excitedly and jumps out from the back.

There’s nothing unusual about the man’s appearance: faded jeans, warm jacket with beanie pulled down. He looks like most tradies in her small fishing town.

The woman leans forward and narrows her focus. She watches until they disappear down the path leading to the cliffs.

She waits. A few minutes later they return, climb back into the ute and chug off down the road.

She has observed this ritual every morning since moving to the town a few months ago. She has scrutinized his movements for any subtle changes to the routine. But it remains the same.

Until one morning, the Mystery Man doesn’t appear.

The following day, the same.

He has disappeared.

She feels unsettled, restless, unable to concentrate.

Where is he?

A few days later, she hears about the Pong Su, a North Korean cargo ship, and the state’s biggest drug seizure that’s taken place off the coast near her town. One man is dead, and several have been arrested.

Her eyes bulge and her heart rate quickens as she reads on. Police are urging locals to report any suspicious activities.

The woman titillates with delight. The normally quiet town has taken on a more thrilling twist.

She immediately thinks of the Mystery Man and lets her imagination run wild.

A drug runner. Observing the Pong Su from the cliffs. A vital cog in an international illegal operation. Arrested. Flung into gaol.

She dallies with telling the police about her daily observations, but hesitates:

What can I say, apart from his ritual of parking near my house? He’s nondescript. I’m light on specifics.

She does nothing.

But the idea of a drug runner still entertains her, consumes her.

Several weeks later, the woman is walking beside the river when she stops to chat with an acquaintance. Jill is well-dressed, a retired academic. They sit together in the sun on the grassy riverbank.

I haven’t seen you out walking for a while, Jill.

She tells the woman she’s been on holidays in Queensland with her husband.

I’m waiting for him now. He’s up on the cliffs with the dog. He goes there every morning checking the ocean. He likes to swim most days.

They hear footsteps approaching from behind.

I’m back. Perfect conditions for a swim, Jill.

The woman turns around slowly. She stares as though having seen a ghost.

It’s the Mystery Man and his dog.

![]()

SQUEAKY CLEAN

JENNY HURLEY

It had all started with my desire to feel connected again, to have a place to call home. My twenties had been lived out of a suitcase. After finishing uni, I travelled, living and working overseas. Unlike most of my friends, my string of girlfriends hadn’t resulted in finding a life-partner, and ultimately, I found myself alone. Tired of living in share houses I decided perhaps it was time to ‘go home’? But where was home? My parents had moved multiple times since I’d left home and were about to become grey nomads.

At first my job search was random – accounting jobs in Australia – but when the position in the small town came up, I started to imagine myself there. Buying a house, meeting someone, even having a family. How had I so unwittingly allowed myself to walk into their trap? At first I didn’t suspect a thing, it seemed like a legitimate business, and they treated me like one of the family. The pay was generous and the conditions better than anything I’d had overseas. I should’ve gone to the police the minute I suspected something was off – when I discovered the off-shore bank accounts – but life was comfortable, and I was well on the way to a down payment on a house. It was just plain stupid not to go to the police the day I found out about the methamphetamine production and distribution.

When we were raided, it was me, the accountant, the police arrested, and then I got their offer: be our fall-guy and when you get out of prison, we will set you up … for life.

Well, I knew I was going down no matter what, so I went along with it. Did my time: my seven-year sentence in a low-security facility commuted for good behaviour and I was out in four and a half years. True to their word, a brand-new car with the address of a house in a town 450 kilometres away awaited my release. I drove there and began my new life.

The small-town hotel I started working in wasn’t even interested in looking over my fanciful, selective resume. They wanted to believe my version of history that had me recently arrived back in Australia from overseas. I was just glad to be free.

Within a year I was a trusted staff member, even helping out the boss with the accounts. I was expected to participate in town events, like when the local footy team needed someone to staff their bar after the semi-final, they asked me. When the boss announced she needed to do a trip to the city, she asked if I’d manage the place. I couldn’t contain my effusive acceptance of her offer. ‘Well, you’re just so competent, love, and you’ve proven you’re trustworthy.’ Did my eyes flicker, just a bit? If they did, she didn’t seem to notice, she just smiled, adding, ‘yep, squeaky clean I reckon you are, love.’

![]()

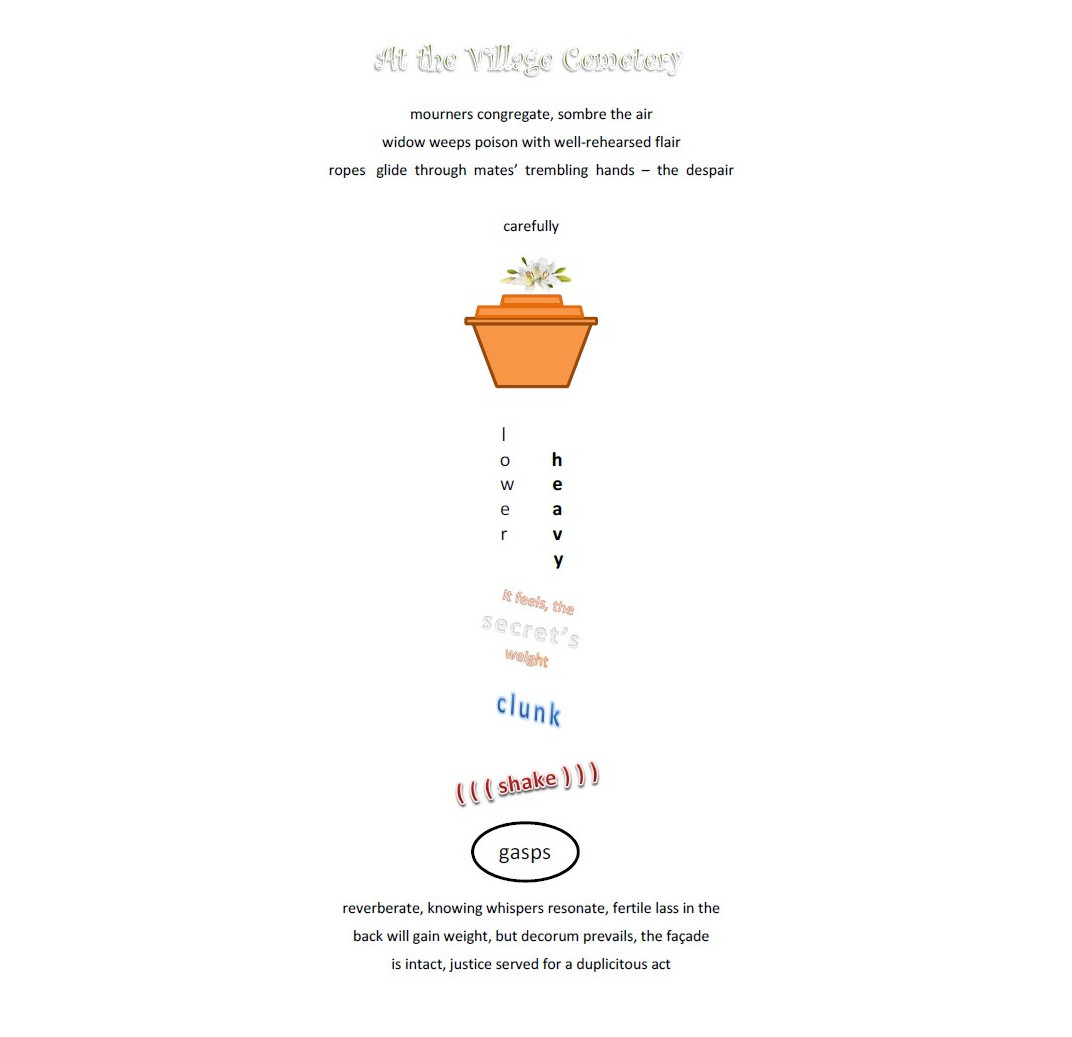

AT THE VILLAGE CEMETERY

KERSTIN LINDROS

![]()

SMALL TOWN, GREEN BUS, BIG SECRET

JOHN MARGETTS

Sometimes the sagging old peppercorn threw shade over our school bus. It was parked across a dusty main street from Traynors General Store, where a line of veranda posts like crooked teeth held up the roof of the only other shade on offer. But that was out of bounds.

‘Wait ‘till I come back,’ the driver growled, speaking into his driver’s mirror, never turning to look at us as we sat cowed on torn leatherette seats. He limped over the road and disappeared into Traynors.

We waited.

Sometimes we all piled out into the railway yard and played cricket. That was permitted. A half-flat tennis ball, discarded fence paling and twenty litre drum did service. But today it was too hot out in direct sun. The lure of a thousand noisy bees and deep peppercorn shade drew us away from sport into the battered old green bus where we waited. Nobody had any money for Traynor’s soft drink. No money for ice cream either. And besides we were warned not to cross over the road. Ever.

It only happened Fridays. The bus left school full, shedding kids at roadside stops like leaves falling off a heat-stressed fruit tree. By the time we reached Traynors only twelve of us remained. The Big Town where our school was had a swimming pool. We would rather have waited at the pool. Instead the peppercorn tree welcomed us, offered its lacy shade and spicy smell.

None of the green bus windows would stay up. If you slid one up in its tracks it would wait like a poised guillotine blade and crash down on an unsuspecting arm. We propped them up with penny exercise books and prayed for a breeze.

A government bore two miles from our farm was where we got off. If you stuck to the shady side of the track you could be home in twenty minutes. Cold water from the rain tank wet your parched mouth and throat before you started on the milking. But for now, we were stuck under that peppercorn tree.

Traynor’s door crashed open and the driver lurched across, carefully mounting two steps and slumping into his seat. He clutched a cardboard box containing a dozen long necks. The box now sat on his lap as he steered green bus on for its final lap.

Over the weekend, a long way from town, the driver would work through the dozen. His Olympian juggling feat eased the passage of getting home for him and us. The long necks rattled a happy little tune that seemed to cheer him and we would sometimes nudge each other as he hummed an old song called Romona. Maybe she was his sweetheart.

Around us the windows scythed down on unsuspecting limbs. It was Friday.

![]()

SMALL TOWN SECRETS

MICHAEL BARROW

Small town secrets, small town lies, small town gossip. I’ve heard it all. Some think I’m a pest and chase me away, but others feed me leftovers and protect me from their dogs who think I’m a pest as well. Some are rude creatures and hurl abuse, but my feathers aren’t easily ruffled.

I like to hang around backyards and make myself look harmless and so I can hear what’s going on. I sit on fences between houses too and listen to the talk between neighbours. Mid-week ladies’ tennis is always good but it’s not just the women; there’s plenty of tasty morsels at the General Store when farmers, truck drivers and dairy factory workers cross paths and at the saleyards too.

But Mary Parker is the queen of the ‘goss’, in our country town, and some of it is some of it’s even true.

‘Margaret Monaghan doesn’t have the look of the Monaghans, does she? No, that olive skin and dark hair doesn’t come from the Carmichael side of the family, or the Monaghans. You’re probably too young to remember but a lot of district farmers took in Italian POWs during the Second World War and put them to good use in the paddocks and helping out with the milking. Well, what I think is that when Kevin Monaghan was taking his heifers to the market, Sheila Carmichael was lifting her nightie for Luigi Valentino.’

‘You know Jimmy Cooke won that shop in a card game, don’t you? Look at him, do you think a man like that would have had enough money to buy a general store, in a town this big? He drinks too, on the quiet and I know for a fact, he hits poor Cathy. Well, she’s always been a bit soft though hasn’t she, especially after the miscarriage?’

‘And let me tell you about Connie Petersen and why she never steps foot outside her house except once a day when her husband has left for work. She’s giving the signal to Curly Sproule, on the rise at the back of the factory. There’s been others too, count my word.’

I was in the plum tree in Robert Embrey’s yard, one afternoon taking my fill when I spied the young curate from St Brigit’s, lurking in layman’s clothes behind the blacksmith’s. He was looking about and checking his watch as if waiting for someone, so I decided to wait and see who he was waiting for. Why? Well, you’ve got me, I like a bit of juicy gossip as well as anyone. Before long a small car driven by another young man rounded the corner and the incognito priest jumped in.

I flew after them in the direction of the Lake and soon found out, perched on an overhanging branch in the carpark, that Father Quinn and Brendan Parker were more than just friends, and what they got up to, was a secret, even Brendan’s mother Mary would have kept to herself. If she’d known.

![]()

A PRIEST’S STORY

IAN STEWART

A mere three years into my profession as a priest, three years spent in a city parish, I was transferred to a distant rural town of just three thousand souls. There were many surprises ahead of me.

I had been used to taking confession from city folk, mostly tales of impure thoughts about people they worked with, petty theft, such as pilfering from the bridge club’s petty cash, or lies told at board meetings. Rural people seemed to have sinned at an entirely different level. Some nights I could hardly sleep for the constant reminders of the enormity of some of the confessions. Small town secrets! You’ll be amazed at what I heard.

During my second week in the parish an attractive, forty-something woman came to me. We entered the confessional. After the preliminaries, her story spilled out. She was pregnant; it would be her second child. The problem was that her husband was not the father. Rather, it was her brother-in-law. He husband, a gruff and easily angered man, had threatened to kill any man who approached her. She was terrified. I did my best to counsel her.

If that wasn’t enough of a baptism of fire for me, the next day in came the mayor. Now, I’d been told that he was a gentle person who was much loved by the district’s folk. Then it all came out – he had been beating his wife again. It was a sin he’d been committing for ten years. He had tried, he said, to stop but somehow she just kept provoking him.

Following this there was a veritable cascade of sin delivered to my door – theft of equipment from fellow farmers, money from the bank, teenage pregnancies galore. The final straw was when a man – a big, burly fellow – came in and confessed to murder! Not a recent event, mind, but a crime he claimed to have committed when he was a teenager. The victim was one of his classmates – a girl he was keen on. She had spurned his advances, which provoked his ire. They met one night. There was a scuffle, he said, and he strangled her.

I checked up later. It had been reported in the local paper some fifteen years before. The crime was never solved. He – the confessed perpetrator – was now a successful farmer with a wife and three young children. What should I do? The confessional – sacrosanct. My bishop, a formidable man, was fifty kilometres away. I could not easily gain his advice. I just had to keep all this to myself.

I kept on for a whole year, administering the sacraments, doing my priestly duty – and, of course, taking confession. I was so relieved when the news came that I was to be transferred to a teaching position at one of the larger city schools. At least, confession there would be about the naughty things that boys did and the thoughts they had. No more small-town secrets to plague me!

![]()

Michael F Barrow

Hi

I’ve recently rejoined Geelong Writers.

How do I send my submission to this Ekphrastic Challenge please?

admin

Hi Mike – email your submission to geelongwriters@gmail.com with ‘Small Town Secrets’ in the subject line. GW

Jan Price

The White Stone Road – Jan Price 1 0f 2

A guest in your town

I ease this gate’s warning

leave the still shadows

of lemon bush and peppercorns

and step into moon-flare

trusting my darker self

forward onto your main road

of white stones

…while you are sleeping.

Around your tongue-hushed houses

you have measured sighing space

before answering to boundaries

yet hinge to a sudden huddle of butcher

baker ghost-sniff of blacksmith

and a few post boxes waiting

morning exclamations.

House and trades

moon-drench to flat greys

yet roof iron ripples graphite-silver

on this frost of pallid muslin

and a dingo-howls for company

over your townscape collage

…while you are sleeping.

On a beacon-yellow porch

a man leans on a veranda rail

one hand drifting prayer-smoke

to dead stars. I invade and wave.

His lips glow-drag a red full stop

then flicks it sparking like fireflies

into his low bush shadows.

His door locks and yellow shuts off

like a reality check on a wistful memory

as I outskirt your town circling back

…while you are sleeping.

Here and there time keepers rise;

the rooster crows the milker bellows

the blackbird liquids dawn

but a hell-loose thundering

bursts from the left with a boy

glued to the roots of its mane

its hooves iron-spark

the white stone road

its wind-sweat streaks past

then a slap of leaves

a crack of ice

and obscurity swallows them whole

while you are sleeping!

2 0f 2

I’ll sit and huff my pen to life;

jot location pace light

and through the sapling hours

question butcher baker priest

in your presbytery over the bridge

and a climb to the hill

for surely they flew dirt by there!

Then with your eggs

flurried from hen houses

your geraniums bucket-quenched

milk froth to your lambs scolded cream

and pattered butter to your tables

your axes at rest in their blocks

your cheeks red-appled at your coals

and your worries droughted to sighs –

I’ll smoke you a mirror of a man

who remembering waits

and like a poet he isolates

breath from length of breath

‘til he fleshes and thrills the dawns

with the spirit of a boy longing for freedom

on the sweat of a phantom snorting

thundering the moonlight

over your white stone road

…while you were sleeping.