Footsteps, by Tom Adair

![]()

STRANGE

JAN PRICE

Strange footprints in the sand —

not a seagull’s scrawny three-pronged arrows

that point in the direction opposite to intended

destination. Perhaps a tide-out early morning runner

for the sand is so smooth, debris may have washed

way out to sea – one would think a shell or two

might have remained, but no. A runner’s weight

would have pressed down the sand, not cupped it

like a protruding bottoms-up cupcake to cool.

The toes are chubby and above sand, not imprinted

as if a left and a right rubber suction-foot imploded

and ran off into the distance – but a runner couldn’t

wear a pair as they would deflate the suction effect.

So, all that’s left is —

Photoshop.

![]()

FOLLOWING ME

MICHAEL CAINS

Sometimes I see footprints. On a beach. Along wet sand. Next to a restless sea

They go nowhere. There is no turning back

Neither do they vanish into the sea from a pile of clothes, for that would be too cliched

Just another pointless suicide, and I’m not ready for that. Not yet

But it could explain the footprints on the beach

Maybe

Maybe not.

I follow these footprints. I see no one in front of me. Just an endless line stretching ahead in the wet sand on an endless beach

Going nowhere – onwards – forever – endless – perpetually – ceaseless – eternal

I stop to listen. Ceaseless waves, beseeching gulls. Wind whistles as it stings my ears. My eyes

I call out, but there is no reply

Just the waves, lapping against my mind, sloshing inside my skull

The footprints murmur softly to me. So I keep following them

Hours pass. Days

They tell me to walk faster, so I run. Distance plods on, irreverent and irrelevant

I tire, but I am no closer. They keep getting further away, and I’m never going to catch them

I try, but I never do. They go on. Always: in my mind.

Then they stop. Abruptly. In the sand, on the beach. They simply end

The waves look away

I leap and spin around frantically, heart racing, not knowing what to look for. Nothing in the ocean, the sky, the sand. The footprints just ended

I crouch like a detective, uncovering nothing. No scrapes, or signs of a struggle. No blood. No alien abduction!

The footprints are gone and my head hurts. My mind is offended they have stopped like this

Without explanation.

I turn and see footprints behind me. A single line of them

They have arrived here. They have stopped here. Where I am. Exactly where I am

I have followed me. I have caught up to me!

My own footprints in wet sand, on a beach, hiding in my mind

My foot fits exactly. I tried, and I know this

I cannot go back into my past; I cannot relive what has happened; I can only keep following a barefoot line of prints in wet sand. On a beach, alongside the waves. In front of me, and behind

Endless footsteps, endless waves.

So I keep going. I follow myself. I can never stop. And neither can they

My footprints. My own footprints.

In my cluttered mind, or on an empty beach. They dodge waves behind me in the wet sand

I follow or I lead

But if I stop, then I die.

![]()

TIME AND PLACE

JULIE RYSDALE

1995 and she watched the rattler of a bus wobble and lurch as it teetered on the barge, masquerading as a raft, ferrying it across Lake Titicaca: a lake disguised as an ocean. She had been shepherded off the bus and onto a tiny boat for the crossing. Her possessions were stowed on the precarious beast, being threatened by a swamping – cause for quiet alarm.

She had been almost comfortable on the rickety, migraine bashing bus, but less so in the confined cabin, below deck in an airless space, amongst flustered chickens. The Bolivian family smiled reassuringly. She guessed they knew there could be worse places to drown than surrounded by lofty mountains, under brilliant cerulean skies.

She was travelling alone from Cuzco to Copacabana on the shores of Lake Titicaca. She readily clung to an uneasy peace on this west side of the continent, far from the east of Australia, her home. The same sunsets would grace here as San Diego, California, or at least she held that romantic image: the fine thread connecting her with a broken relationship, still woven around her.

…

It’s easy to collect strangers when travelling alone. That’s how she met Paul in Cuzco a few days previously. He had also travelled to Copacabana and occasionally they dined together, his easy manner and knowledge of Spanish a most definite advantage.

Paul’s final day found them hiking up to Cerro Calvario, 4,000 meters above sea level, on a hill overlooking the shores of the vast lake: the solitude and splendour of the moment holding them captive. For the reason that we reveal ourselves to people we will never see again, she shared her distress and guilt at a failed relationship with an alcoholic she had known in San Diego. He was a good man, a very clever, well respected man, who drank and became bleak and her heart always clenched.

On that tranquil hilltop, intense ideas materialised that before had only been apparitions. It was her fault the relationship failed … she should have done more … if only she had offered reasons not to drink … if only she had resisted asking him not to drink. If only she were a better person …

Framed by the endless lake, speaking softly and without judgement, Paul spoke of how he too had been an alcoholic many years before. He spoke of how he destroyed his marriage and his business. He spoke of how it consumed him, rotting his world.

He spoke about how it had been his failing and his alone. He spoke with simple acceptance.

With the power and wisdom of the Andean mountains before her, she felt his words bringing change, her breathing softened, she felt lightness and clarity. She became the stillness she yearned. Gently, profoundly, freedom welcomed her home.

She never saw Paul again, but never forgot him or how, high on that Bolivian peak under that cerulean sky, he helped her to walk freely, and truly on her own.

![]()

trapped footsteps

jo curtain

![]()

A SEA STORY

NATALIE FRASER

I can’t keep going. The words just won’t come. I’m otherwise occupied, staring out at the dark blue ocean. The day is stormy, the ocean heaves and throbs and I’m remembering his footprints in the sand as he tried to run away from me.

On the beach the freezing winds blow straight from Antarctica. He now lies spread-eagled on a rock. His head is turned towards the bleak sea, hair blown flat to his skull, and I know, without looking, that his eyes are as cold as, as grey as, the cold grey sea.

Hours later he is still there. A shadow in the encroaching darkness I can see him but dimly. My eyes squint through the glass of the picture window as I try to make him disappear. Out there is chaos, floating on the windy sea. Sometimes he is there, sometimes he isn’t and sometimes he has merged with the milky dusk.

The wind whips my face as I walk on this winter beach in the first dawn light. I’m alone with the ebb and flow of the ocean; it is as inevitable as a heartbeat. He is no longer sprawled on the rock. There’s only the memory of him as I watch the water washing over it. I trace patterns in the sand, a jagged line like a scar, a vortex swirl. I run, dodging the waves until I trip over something. At first, I think it is driftwood that has washed up overnight but no, this is an arm, covered in a grizzled grey jumper. This is a body, face down, the thin strands of hair lank and writhing in the water.

Like a kid trying to attract its mother’s attention, I’m tugging on the arm. I’m scared that if I tug too hard the arm may come away from the body. I don’t want to be left standing here with an arm, what I want is the body. He was human once. He is human now though his flesh hasn’t the elasticity it once had. The sea, on the other hand, is a living thing. From the tiny krill to the larger mammals, it teems with life. As I bend to look at him, I see that his body has already provided space for the smaller parasites; minute, crab-like creatures inhabit his orifices. On the sole of his shoe, I find a lone barnacle clinging.

I watch the house in the rear-view mirror until it has become a tiny brown smudge in the distance. I can feel a weight in the passenger seat; he is there, his jumper so thin. I’m elated as I spin the car around and press my foot on the accelerator. The edge of the cliff looms. Soon I am floating on the windy sea; beside me his eyes are cold and grey. He is here with me, and we are floating on the windy sea.

![]()

material poverty spiritual richness

john heritage

![]()

QUESTIONS

GEOFFREY GASKILL

Stig hadn’t meant to follow the footprints that morning. He hadn’t meant to do much of anything except … that. Those marks in the sand took his mind off … that.

It wasn’t just the footprints. The sand was pristine, unmarked by human hands, as it were. Only human feet, it seemed. The trouble was those marks made no sense. They didn’t belong. While he had his thinking cap on, how, did the rest of beach get to have no other marks of human passing?

The place was pretty in a garden-of-Eden way, but somehow struck him as sterile and even … spooky.

Then there was the lack of noise. No shush-shush of waves crumpling upon the weed-crusted littoral, no gulls, no people, no … anything. For all intents and purposes, he might have been witnessing the third day of Creation.

Stig looked around. His childhood Bible studies told him, God said let there be waters under heaven and let the dry land appear. God called the dry land Earth and the waters the Seas. People, he remembered, weren’t created till the sixth day, so if this was some religious flight of fancy, there would be nobody to leave those mysterious prints. That meant that he too shouldn’t exist.

He shook himself. If the fantastical was needed, he could just as easily be in the middle of a dream-version of Pooh Bear chasing the Woozle. Except he couldn’t see anything that passed for a hundred-acre wood.

The questions of how and why he was here floated miasma-like around him. Where was here? ‘How do I get away?’ was his next, obvious, question. He may have spoken aloud but no sound had come. The place was as silent as the grave, as the saying went.

‘What the …’ he screamed but the sound only thundered inside his head.

Pushing down panic, he told himself, ‘Be logical. Think. What did you come here to do?’

That was the answer.

That.

Therein lay his problem. He had no memory of doing that or proof he’d done it. He’d felt no physical sensation. He was sure he would have remembered that. Come to think of it, he felt nothing now. All he could recall was suddenly being aware of the beach and then those prints.

Maybe the silence, the beach, those footprints were all telling him he had, in fact … he gulped and took a breath before conceding … he may have succeeded in doing it.

If so, his logic went, he expected more to … he found it difficult in articulating where this was leading him.

He’d read somewhere, if you eliminate all which is impossible, then whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.

Was that truth that here was some sort of afterlife? Heaven perhaps?

He looked at those footprints that meant nothing and lead nowhere, at the emptiness of the beach and he listened to the silence. If this was Heaven, he concluded, what might Hell be like?

![]()

NATURE’S CLASSROOM

JENNY HURLEY

Ardie stares at the clock, chin resting in her palm, pen poised: twenty-eight minutes till the bell signalling her release. Ms Smith has made good her threat that if she failed to submit her homework one more time, she would serve a lunchtime detention. She knows her teacher will be annoyed with the paucity of words on her page – should she tell her the real reason for not handing in her homework?

…

There is no evidence of life at the shack. Peering through the flyscreen, I see an empty table and dishes in the sink. Talia hasn’t waited for me, so I return to the tea-tree sheltered, meandering path and soon feel the full force of the wind as I set foot on the beach. I kick off my thongs and head towards the water, stopping just short of the water’s edge to roll up my jeans. Where is Talia? Scanning the beach I see one lone fisher, and in the opposite direction, I notice a trail of footprints. Squinting, I can just make out Talia’s form. I quicken my pace and begin to wave and call to her.

We had become friends the first summer that I started coming to the island with Dad. It was the year my parents separated. When Dad suggested we go for the weekend, I leapt at the chance.

But what about your homework? Mum asked.

I’ll take it … I’ll do it there, I promise, I beseeched, and Mum relented, tucking my homework book and pencil-case into a cloth bag.

I’d spotted Talia in the mainland general store. It was always busy there on Friday nights. I sidled up beside her, making her jump.

What are you doing here? Is it school holidays already? Talia is home schooled and not always au fait with the term schedule.

Nah, we’ve just come for the weekend.

Where’s your old man?

Same place I reckon yours is – the pub!

The ride in the tinny to the island always transports me into holiday mode. The high-pitched sound of the outboard motor and the bump-der-ker-bump across the lake to the island is thrilling, especially under a night sky. I love jumping from boat to jetty, grabbing the rope Dad tosses so I can loop it over a jetty post. As I stood on the jetty on Friday night, catching what Dad lobbed up to me from the boat, I never noticed my homework bag languishing on the floor of the boat. It was not until our return trip to the mainland, late Sunday afternoon, that I saw it. Oh, shit.

When Dad woke me on Monday morning, I couldn’t remember the car trip back to his place. Had he carried me from the car to my bed? Quick, eat something and brush your teeth – you don’t want to be late!

…

Ms Smith’s inscrutable gaze goes from paper to her student’s face and back again. Ardie couldn’t tell if her teacher’s lips were curling in disapproval or hiding her smile.

![]()

INTERPRETATION

IAN STEWART

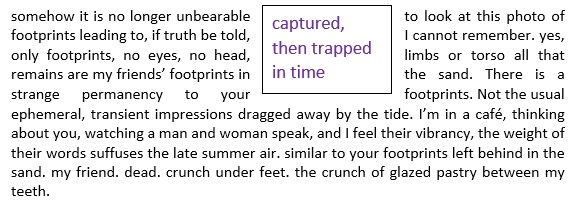

Look at the image. You will see eight disturbances in the shape of footprints on what could be a beach, heading in a line away from the observer. There are eight. The furthest one from us is just discernible at the top of the image.

Let us take the elements of the image one by one. First, the background: yes, it probably is a stretch of sea-washed strand. No shell or seaweed fragments to be seen. It is perfect – was perfect until imprinted by a person unknown …

Are we then to believe that an unknown presence has recently walked in the direction we are looking, or maybe walking, too?

I think that such a synthesis of the situation is too simple, too pragmatic. Look again and you will see that the ‘foot images’ are not imprinted in the sand but seem to stand up in bas-relief. If that is so, then we must look for another, a different, interpretation of the image. So, a story emerges …

Thetis has taken her son, Achilles, to the edge of the River Styx. She holds him, inverted, and immerses him in the waters, knowing that this will confer invincibility on him. Yet his heels, by which he was held, are not gifted so. Will his weakness be discovered? Not yet, if the image before us tells of Achilles’ power and might. His invincibility allows him – actually confers on him – the power to raise the places where he has placed his foot, into relief. This draws attention to his might and differentiates him from the mere mortals who populate his army, who leave indented footprints wherever they go.

All stuff of myth and legend, you might say. Of course, that’s always a possibility when looking at and into a work of art such as this Tom Adair image.

Footsteps?

Maybe …

![]()

HE’S GONE

FRAN GRIFFITHS

He’s gone

Back into the deep

Like seaweed lost he yearns for the deep.

Or is he a she

Who remembers another world

When she reigned in the mer world.

Or are they just it

As they watched a sunset that afternoon

And swam naked in the sea

And then became one footprint

Along a wide Sandy beach.

![]()

IN THE FOOTPRINTS OF A GENTLE GIANT

ALLAN BARDEN

Gundar Ryder was a good man, a true gentleman and my good friend who cared about others, especially children and those less fortunate. As a teacher at Darwin’s Rapid Creek Primary School, the children revered and respected him. Being well-muscled and tall, Gundar was known as ‘the Gentle Giant’ by his friends and colleagues.

I met Gundar in Darwin in the 1970s when as a player for the Nightcliff Football Club, I accepted his request to the club for help coaching his school football team. As a former Newcastle NSW lad, Gundar knew little about Aussie Rules but much about rugby league.

The majority of the team were of Aboriginal mixed and varied family backgrounds and either orphans or in foster care at the Bagot Road Reserve and the Retta Dixon Home. Many had experienced a disjointed family life including violence, alcoholism and crime.

As coach I became known in the local Aboriginal community, as the ‘white fella’ in the green and white HD Holden sedan who, every Saturday morning, collected boys from the Reserve and the Home to play in the junior AFL competition. That ‘white fella’ who drove along Bagot Road in a car bursting with excitable Aboriginal boys wearing green and gold football jerseys.

In my third and last season as coach, we won the Darwin Primary School Football Premiership with a nerve-wracking 1-point win over the highly fancied and very skilled St Johns College who had won the title for the previous 10 seasons. Beating St Johns for the premiership and witnessing the proud expressions on the faces of those young Aboriginal boys remains one of my proudest memories.

I was saddened to learn of Gundar’s passing several years ago and often think of him whenever thoughts and conversations of Darwin and the Top End arise. Gundar dedicated 34 years of his life as a classroom teacher of mostly Aboriginal children at Groote Eylandt, Jabiru and Darwin. He loved classroom teaching and refused transfers and promotions to keep doing so.

I remember fondly our wonderful conversations about his childhood in Newcastle, his weightlifting exploits, his love of rugby league and the stories about the immigrant child from Latvia who fled to Australia with his mother at the height of WW2, leaving his father behind in the Stalin controlled USSR. Gundar finally traced his Dad and visited him, but with great difficulty, as Latvia was part of the former USSR.

I wonder sometimes where life may have taken those small Aboriginal boys who played football without boots and whom Gundar loved teaching and I loved coaching. I hope that for each of them life has been happy, healthy and rewarding. I hope too, that they remember with great happiness what they achieved against the odds all those years ago with the assistance of ‘Mr Barden’ the ‘white fella’ coach and the dedicated immigrant ‘white fella’ school teacher known as ‘the Gentle Giant’ who left behind huge footprints to fill.

![]()

DESTINATION

JENNY FUNSTON

I trailed along looking for meaning,

Silent retreat on golden sand.

Footprints, not mine.

Are they a sign meant for me

or a purely synchronous occurrence?

Courageous confidence nudges me forward

to explore, engage

in a world gone mad.

Withdraw!

Why?

Unknown, yet tempting.

Gurgles of fear pour through my gut,

Rendering me momentarily powerless.

Suddenly, stillness

takes my hand,

Gentle footprints, not running,

but leisurely walking

Thus leading me on.

![]()

FOOTSTEPS – A HAIKU

SUZANNE MILLER

Alone on the beach

heavy thoughts blowing away

– my steps grow lighter

![]()

BABY STEPS, ANYONE CAN DO IT

CATHERINE BELL

I didn’t tell my family what I was about to do. But I was turning seventy, and in a mind to shock them.

The instructor looks directly at me.

Don’t think about it. Do it.

Run, dive, drop, roll.

Baby steps. Anyone can do it.

She’s slim, athletic, and her take no prisoners attitude puts me on guard. It’s only the first lesson, and already my heart is thumping.

I sit with the other equally white-faced skydiving students in the hall, as she bombards us with dazzling aerodynamic facts.

She paints a mind picture of skydiving, holding her arms open to the heavens:

Awe and wonder, it’s all awe and wonder.

Rising panic moves quickly from my stomach to the upper reaches of my throat. I’m not experiencing awe and wonder, just sheer terror.

I gulp huge mouthfuls of air.

The group goes quiet as the instructor ramps up her spiel. She describes the free-flying, head-down position with terms like terminal speed and 250 kilometres an hour.

Then she explains:

Your first task is to simulate a skydive at 4,000 metres.

I dutifully follow the group and climb onto the stage. Those full of adrenalin, scramble to the front of the line.

I slink towards the back.

In one smooth manoeuvre, rush to the front of the stage, dive off the two-metre edge, drop and roll onto the floor below.

A tight band forms around my chest and restricts my breathing. I’m shaking with fear, and I haven’t even left the ground.

Someone attempting to break the tension shrieks:

Charge like a wounded bull and yell Geronimo.

Those in front of me disappear over the front of the stage in quick succession.

As I edge my way closer to the top of the line, I’m unravelling inside and feel like a condemned prisoner.

My stomach suddenly flips, my feet heavy with dread.

I close my eyes and make a limp lunge for the drop, bleating:

Geronimo.

As I reach the precipice, I hurl myself into the abyss. A heap of flailing arms and legs lands awkwardly on the floor.

I’m slow to rise, and the person behind me in the line, a rotund, Babushka doll of a woman, lands with a thud next to me. She knocks me back down to the floor.

I hear the relentless voice of the instructor echoing in my head:

Just baby steps today.

In the next lesson, you’ll learn ways to reach higher speeds by streamlining your body and minimising body drag.

This is not what skydiving is about, being in a dusty church hall. It should be all blue sky and sunshine, fluffy white clouds, a parachute of silk floating me gently down to earth.

And I’m not a thrill seeker. Why did I think leaping out of a plane and plummeting down to earth was such a good idea?

All I want now, is to evaporate into thin air.

I pick myself up and bolt from the hall, out into the sunlight.

![]()

Leave a Reply