Waiting for Rainfall – Winton Wetlands, by Jo Curtain

![]()

CYPRINUS CARPIO

KERSTIN LINDROS

life—it’s not easy for me, a common old carp, survivor of many battles in the ponds of Saxon forests, who sings when scared but no-one hears, who pays mindful attention to the lustrous dragonflies that hover and dart in the element of the free from down below within my murky realm, to hold out, year after year after year—

as a fingerling, you flee into dense reed forests when the black cloud descends to dive in for the kill, panicked heart beating, body quaking, fear lingering as your friends disappear into hooked beaks, before the predators posture on posts, soaking wet wings spread wide, bellies full, brains blissful from dopamine explosions, and you count your lucky stars and dream when the night blankets your waterbed, eyes fixed on the sparkles through the near-still surface after yet another dusk feed, you made it this time but the attacking cormorant army grows daily, even recruits foreign squadrons passing through

on the good days you swim in the upper storey, luminous with filtered sunlight, or near the shallow edge where small and large feet stir the mud in playful rhythm, you leap, hoping to be included but go mostly unnoticed until you brush a torso or a limb—some laugh dismissively, most shudder in disgust—so you freestyle off into deep, dark pond central, embarrassed, crushed, but safe, and later follow the human shadows promenading on the banks and listen in on conversations—are they friend or foe

on the autumn morning when your world is drained, when men in waders drag their nets through your muddy pool, now shrunk, overcrowded and ready for harvest, a 500-year-old tradition, the grey water turns golden as scales reflect the morning sun and whiskers flicker, fins thrust—trying to reach the edges, hoping to get away—while the whistling wind smothers your attempt at a song that turns into a whimper

few of my size escape the dreaded mesh but if you make it, you close your eyes while half your family is resettled, temporarily, in big tanks to await the annual fish and forest festival, a celebration of our lives, finally acknowledged, loved and valued (in €)—poached, smoked or as pate

i’ve come so far, and now? i live another year, with all of life’s uncertainties, with bouts of melancholy, but hope glimmers on—

![]()

FRAMED DISEASE

HAO ERN (ANNE) FO

Disease is a subtle beast, only nameable by pandemic. Unknowable in the veins, infused, silent

into the skin.

It takes many forms, fuzzier, louder, bile sliding down it.

No one could escape it in the streets.

‘Hello?’

It bites into their necks, inducing blood out and into trails; red, hot lines painting the road. Then

they fell, like littered brushes left unused, wasting strokes into the ground, as they sunk into the

canvas of the town. Sunken in cheeks, the pallor of thinning oil, and their eyes; the eyes. It was

swollen from a dead fish’s stare, glossed over and plasticine, garbage bags scrunched into the

pupil— a stink residual at its pits.

‘Anyone?’

I felt warmness swell in my throat, the lungs mass producing in rot, as I ran into the woods

nearby. Away from the bodies, the beeping cars and the deficient buildings, replace it with bare

trees that struck out like wrinkled fingers. It held the barely salvageable earth together, knitted

together in a mess of stringy grass that stung as I crawled past.

‘Oh god-‘

That was when I gazed upon it, the beast, the monstrosity of some cartoonish design. A gray

fish, drifting in air simply, eyes like those who had already rot but its mouth was open, hanging.

Instead the red is embedded in its body, seeping through the flesh as orangish-brown spots on

skin. The fuzzy ring in my ears returned, cleansing everything of the trees rustling, the birds

crying, the smoke that swore, of the blood proceeding from my mouth.

‘Please’

I never saw the fish coming but it swept around my side, a sweet companion nuzzling in my hip

like a sick dog. I didn’t know it, it didn’t know me. But neither of us could care, as disease is so

simple. Animalistic, a companion that stays in a living body, parasitic, end.

‘…’

So I fell into the ground, like the many others, sunken, painting the ground in earthy hues. And

the fish left waiting, subtly, unknowable, a harbinger of everything and nothing; and it brought art

with it.

The town, Winton, left as a collapsed artwork; all casualties till now are sincerely dead.

![]()

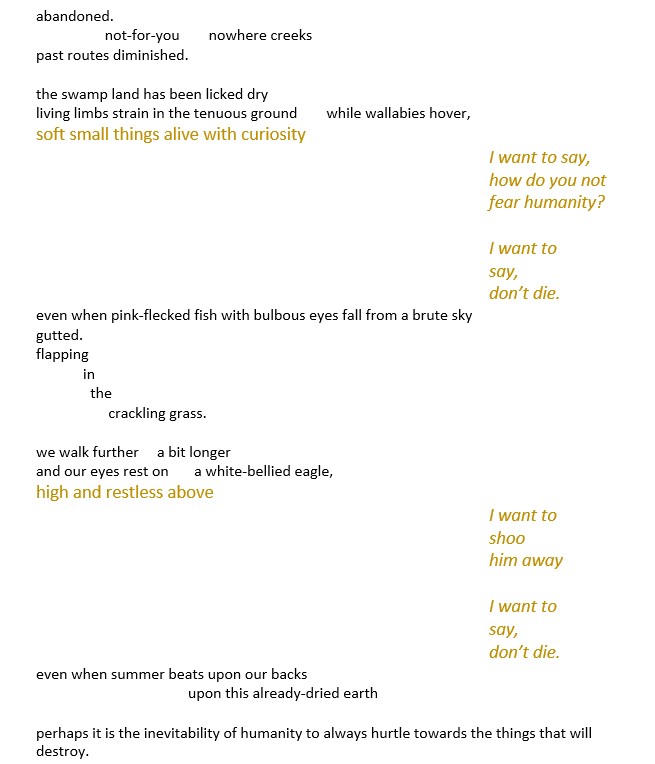

just add water

jo curtain

![]()

DROUGHT’S END

ADRIAN BROOKES

Little creepy knows Death has turned his gaze on her; insignificant as she is, the merest fleck on a speck of the biosphere, the crawly bug yet discerns the Reaper’s flawless diligence that renders him incapable of neglecting even such a scrap as she. Already mortality’s cold shadow is blunting the edge that hunger lent her senses. And yet—and yet!—from the parched creek-bed there comes the reek of a death not her own. Another dying thing! And death not her own means nourishment, both for herself and for the eggs she will lay.

Instincts strain to focus. Down the bank, stumbling across grains of dust where once cascaded a stream, the creepy thing creeps, her fading wits craving the succulent carrion. And there!—in the last shallow puddle, gills flailing hopelessly for breath, mouth kissing air in futile pursuit of its element, there wallows a fish.

Not dead yet—but not far off! Just a little wait…

Crawly bug hunkers down, watching, willing. But the air is darkening, heavy and steamy, smelling like fog, and soon a pitter-patter, patter-pitter crashes all around her, tossing grains high in the air.

There’s a stirring behind the great fish’s eyes, some new sentience of hope. Its fins begin to wave as its element, the creek, sweeps back in and swamps it, washing away the dust. Floundering no more, the fish drinks afresh of its former life and, famished from its wasting, hunts again for sustenance.

And with a gulp little creepy is gone.

![]()

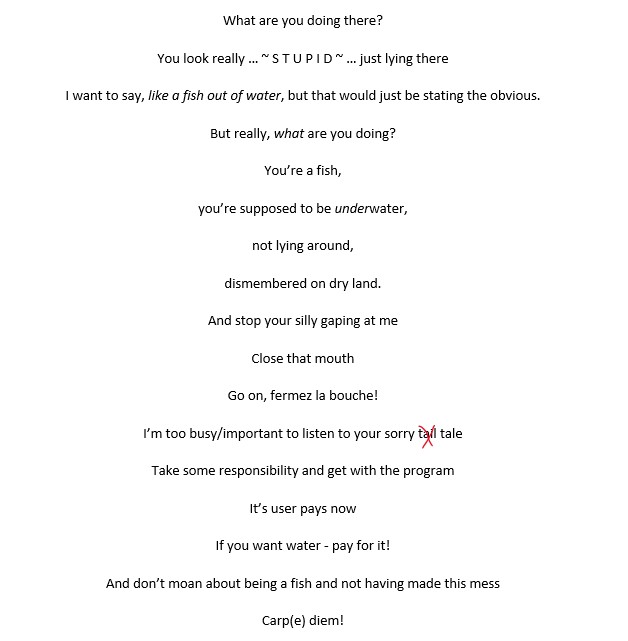

CARP(E) DIEM

JENNY HURLEY

![]()

WILL IT MAKE THE HEADLINES?

JULIE RYSDALE

The jet’s contrail alerted the possibility of a storm above the Death Valley terrain

Dagan spun the pedals faster and cruised down and around the sweeping bend

The air had a quiet chill to it, the breeze skittering off his bare arms

Tiny robust wildflowers were starting to shine their brightness on the harsh salt flats

Already the Basin was starting to be tenanted with tiny pickleweed,

An unexpected delight to the many tourists who stopped and stared on Spring days like this.

Even now, the sightseers were trekking the landscape brushed as a watercolour

His sense of belonging nestled here, despite its countless fair-weathered friends.

The Joshua trees high above the Basin were no longer the lone vegetation as life continued.

He felt he could sail the moon and find nowhere more beautiful than Bad Water Basin

Crusted, salty and white, the surrounding mountains its guardian

‘Specific drying times and salt usage must be followed.’

Desert Gold and Sand Verbena were starting to bring brilliance to the blinding flatness of colour

He saw their promise, but his heart was elsewhere.

Myriad times Dagan had travelled this road studying the wane of the Salt Creek Pup fish

A failure he played in their conservation

‘Dried fish was a valuable product in times past.

In this day and age, we have access to refrigeration.

It is not usual to dry or salt fish.’

But today was different. Today he cycled and he travelled alone

To his right rose the Artists Palette, a special place for him, and would always be

He turned and climbed the steep gradient feeling his breathing quicken

A masterful artist had orchestrated a rainbow symphony amongst the boulders

Their volcanic beginnings painting the music; a place of great hue and reverence.

He knew today would forever change him, the devastation he felt keenly, deep and menacing

No longer frontpage news, no longer the debate of beer-soaked gossip. Now, a god unmasked

His advantage was that the final story would be his and his alone

‘Find your own special recipe!’

The first fish hook pierced the palm of his hand, in the beginning gently teasing the skin

Then pain sinking deep, with its taunting hook twisting to the sky

The blood took a while to trickle and seep, adding lustre to the palette, a witness to his crime

The second, he raked along his wrist, penetrating the life pulsing artery vibrant and energetic.

Below, the road stretched into the vastness, ending at a gaping hole where his heart should be.

![]()

AT DUSK, AS I URGED THE FISH TO BITE

MARK HEATHCOTE

I remember the lake-light shining

like a disk as I fished for perch or pike

at dusk, as I urged the fish to bite,

bite a spoon of shimmering bait.

I remember bats flitting and circling

like the insects, they longed to catch

and ripples left by fish that were no match

I remember Father’s blunt roll-call home!

The boathouse, a sarcophagus

with its two-well-rotten doors

gaping open like-malnourished jaws

awaiting Death’s ferryman back,

back to those perpetual, keepnet-shores.

I remember the rolling fog rising

about the gnarled chestnut trees

billowing out into brackish red reeds

and a slice of scaly moon leaping:

That frantic-fish pulling line from my spool.

I remember the lake-light shining

in the scales of a real living-ghoul

plucked out of the water fighting

a fish – that wasn’t one-bit preschool.

![]()

ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE RIVER

GEOFFREY GASKILL

Murray was missing. No-one had seen him for some days and that didn’t bode well.

The first to mention it were Goldie and Jungle, the Perch sisters. ‘Haven’t seen him for ages,’ they said. Goldie and Jungle had been vying for Murray’s favours since they’d strayed into the river a few years earlier. They’d been known to wait outside the entrance to Murray’s hollow log each morning in the hope that fluttering fins would attract him.

‘Murray is always there,’ a worried Sheila Smelt agreed. Sheila was small and silvery, but it was her jitters that put everyone on edge. Behind their fins, they called her both silly and stupid. Sheila’s obliviousness did her no favours. Murray was her rock. ‘He’s wonderful,’ she gushed.

Mangrove Jack, not one noted for hasty pronouncements, commented on the unfortunate coincidence of Murray’s disappearance. ‘Not long after Barra went up,’ he said. ‘Significant? I think so.’

At the word, up, everyone paled. There was much rolling of eyes towards the surface of the water. Up was unknown. Up was to be feared. One time Murray had tried to calm their fears. ‘Up is fine,’ he said, before adding darkly, ‘unless you see the shadows.’

‘Shadows?’ Sheila had squeaked and hid behind her rock, followed by her friend, Saratoga. Shadows portended disaster. Sooty Grunter had been the first to make the connection. Not long after, Tamar Goby, then all the Galaxsias boys as well as the unpopular Talapia went up on days when there were shadows.

Mangrove Jack nodded in smug superiority

Up was a byword for a world beyond the familiar world of the river. Though what was there, none could say. Murray once told them, ‘Once you go up, you don’t come back.’ Up became the word to frighten the small fry.

Perce, no relation to Goldie and Jungle, was the only one to survive going up. He was so traumatised, he refused to talk about it afterwards.

Murray was exasperated. ‘But you must have seen something.’

Perce shuddered. ‘I don’t want to talk about it! The pain … The pain … is indescribable. Best to let sleeping fish lie,’ Perce suggested. ‘Why upset the others?’

Murray looked thoughtful and nodded in agreement.

Up, therefore, remained real but elusive. Bacoo Grunter and his cousin, Sooty, said it was Perce’s duty to tell all but Murray declared, ‘We should all respect Perce’s right to silence.’

Bacoo bubbled with indignation, but Murray was as stubborn in Perce’s defence. The matter went nowhere.

Then Barra Mundi went up. A day later Murray went missing.

No-one wanted to say the unspeakable. At last Perce declared, ‘We may have to accept that Murray has gone …’

The rest couldn’t bring themselves to use Murray and Up in the same sentence. The list of uppers was getting depressingly long.

‘What now?’ Sheila asked, trembling, just as a shadow passed over the riverbed.

All eyes turn up.

![]()

TOXICITY

MICHAEL CAINS

Emerging from dark seas,

eons ago.

Crawling from slime to the land,

Time passes,

Evolution.

We fish then became you,

Some staying.

In our seas, rivers and lakes,

Just waiting,

Devolution.

We watched your land dying,

our water.

Death lurks around every bend,

Climate change,

Pollution.

Poisons, fires, endless floods,

Toxic Shock.

You’ve destroyed our habitat,

We’re dying,

Desolation.

Lie gasping on the banks,

glazed over.

We cannot turn back the clock,

time ending,

Discontinuation.

![]()

CYCLE OF HOPE

DAVID BRIDGE

The Fish and Chip Shop float had, like much else in the Spring Parade, been swept away by the torrent. Now, months later, its torn fragments draped the fence stumps that marked the boundary between mud caked farmland and woodland blighted by weeks of waterlogged roots. Grasses and weeds, encouraged by the early summer warmth, put in a sickly performance decorating the open spaces, but little seemed able to draw nourishment from the sour smelling ooze abandoned by the receding waters. The promise of Spring rain, for farmer and shop owners alike, had turned into a dead hand over the region.

In town the passage of time had similarly left its mark. Tattered remnants of the decorations that the High Street business owners had hung above their doorways still clung here and there, the gawdy colours now faded and mud splashed. Back numbers of the local newspaper told of high-pressure hoses wielded by community spirited local plumbers driving out chocolate rivers of sludge from shop front after shop front. Volunteers from the local football and fishing clubs pitched in to cut and clear oozing carpets, squelching to and fro until mops and brooms could be brought to bear. Curb side, mounds of ruined electrical goods and warped furniture rose as monuments to what had been lost before being bulldozed away.

For many days, anxiety prevailed every time clouds formed overhead. Gradually, river flood markers charted the lessening flows from upstream, though sandbags remained piled along pavements, held in reserve in case the weather gods felt moved to wrath again. Folk, who had once looked hopefully skyward for showers to help sprout grain and put wages in local pockets, filled bottles from water tankers to tide them over. Black bilge from run-off suffocated what little life remained in dwindling pools.

Yet, out of this adversity the refreshed sense of community drew together those whose lives had been so disrupted. It would be a while before the cafe and fish shop would be back in business but their owners could see the possibility once more, and downturned mouths lifted as conversation about the future became more animated. Now, youngsters sick of gawdy gumboots joyfully donned playground footwear once more as temporary classrooms settled on new formed slabs already blessed by local politicians in hi-viz. Relieved parents gained needed hours in which to pursue lagging insurance claims and track scarce tradesmen, at least for those with hope of rebuilding. For all too many, livelihoods remained on hold while businesses took stock.

In surrounding fields, stunted remnants of a first planting spoke of stretching overdrafts and difficult conversations ahead. Rescued machinery stood sentinel by part spent hoppers of seed, hostage to negotiations with creditors. Ironically, only forecasts of rain to come would see soil turned and new furrows primed. Yet, this was the gamble of generations, the belief in the cycle of the seasons paying back more than it took. One by one, tractors laid down the first bets on the next round.

![]()

HEART STOPPING

JENNY FUNSTON

My god she cried!

Ripped from the heart of living,

Beseeching, imploring,

Gather your resources, share, teach.

Stark, distressed timber limbs,

Images heart stopping.

Is it me, or is it you

who renders our Earth impotent?

Sucked in by the ‘good life’,

Dis-embowelling the very essence of our sustenance

Look at me!

Look at me!

Look at ME!

Cry, reflect,

A glimmer of hope

REIGNITED!

![]()

THE SWEETEST SMELL A PLUVIOPHILE KNOWS

CATHERINE BELL

Don’t look at me. Don’t touch me. Don’t talk to me.

I’m prickly and irritable and fly off the handle at the slightest provocation.

It’s the heat. It does strange things to me. An outside force takes over my mind. I’m hopeless and powerless when the temperature climbs in the summer.

Heatwave after heatwave. How does anyone cope? Weeks of relentless, sweltering high temperatures and hot summer sun pounding a tin roof.

We don’t have any real insulation in the roof, just a thin layer of tinfoil. All the other farms are the same. No insulation, no air conditioning, no relief.

I know we are in for a scorcher today when at first light, Dad like a ship’s captain with his loudhailer, booms:

Batten down the hatches, NOW.

I spring out of bed and slam shut windows and doors. It is our only defence against the heat.

And then we sit around waiting.

Waiting for the cool change. Waiting for the rain. Waiting for the autumn break.

Always waiting.

The morning sky is a furnace. Sunrise of mackerel and coral ripples and spreads out from the horizon, like a giant fleece thrown across the sky.

There is an air of dread and inevitability as we wait for the day to unfold.

By mid-morning, the heat has pervaded every crevice of my world. I can smell it in the air, feel it in everything I touch. Hear it in the cracking of the tin roof and the relentless buzzing of blowflies.

The heat is inescapable; a force so powerful, so all-consuming, so threatening, it renders me totally useless.

The dogs are listless, limp, sapped of life; the garden eerily quiet. No birds to be seen or heard. Just the odd dragonfly swooping and gliding through the air feasting on insects.

Beyond the garden, the baked, bare paddocks are reduced to dust bowls. Sheep gather amongst tussocks of dry, flaxen grass under the spreading redgums.

By late morning, the northerly wind is menacing. The thermometer climbs to a sweltering 40 degrees.

Still waiting. Waiting. Waiting.

And then it comes.

The wind turns. The temperature drops. Slight zephyrs at first, then gusting and swirling, coating our farmhouse with precious topsoil from the paddocks.

Cumulonimbus rain clouds billow in the west, threatening to empty at the slightest invitation. These black-bellied thunderheads clatter and rumble, as lightning ignites the pulsating purple sky.

I smell the petrichor, the earthy smell of first rain kissing dry earth. It’s the sweetest smell a pluviophile knows.

Rain thunders down, the pounding of a thousand drums. It’s deafening. It’s pure delight. It brings relief to our home. Our paddocks heave a collective sigh.

Windows are thrown open and the cold moist wind sweeps through.

The tension of the day evaporates.

I breathe again.

![]()

Jo Curtain

Enjoyed reading these wonderful fishy tales and creative responses to my image :))

Jenny Hurley

Thanks for the inspiration, Jo!

Kerstin Lindros

I love your artwork, Jo, and all the writers’ varied responses to it.