things aren’t what they seem, by Jo Curtain

![]()

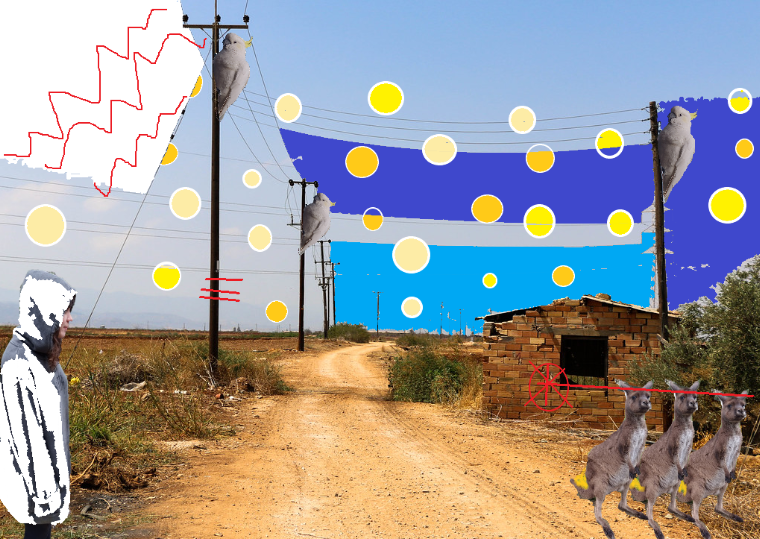

KEEPIN’ IT REAL

JULIE RYSDALE

So there it is again, fools. You disjointed souls mocking us mules.

Taking us for a ride now. You are drawing us out? how?

No use hiding in the red sand, watching from the dry plains,

You are all that fine knobby dust. You are remains.

No point praying in the daylight a road train will squeeze right past by us

and give me some love/love/love

or a keg of ale.

No sense hooded in the dark night or a blacked out/bricked out hidey hole

only the dullards amongst us would use for a kip, take a hip-nip.

Unless you want us to use it for its intended purr-pose …

Climb inside for a rocket ride!

Hey, don’t look back at the sandy soil disappearing, tiny dots? or the airship blip blimp

… could be that poor dizzy Baker chimp … and you don’t wanna see his fear!

Keep it moving, fire it up baby!

Rocket launcher, blue skies awaiting.

No bodies know we are fighting, or even writing

keep it floating,

push it upward? how? There we go now!

Hip/hop/hop/hop … Watch my tail, hey!

Oops lost some loving, yellow loving … floating outwards,

mind the skies there … losing height, wow! Try and grab them?

Keep it steady there … out beyond a moon now.

Can. We. Get.

Where?

Who said not to breathe here?

I’ll suck the sky white, chuck a fit and blow it out … heady cornflower, is that cerulean?

Hit the button,

change that colour!

Who hung the washing out? Mind the knickers, kind of kinky.

Draining power now, feeble efforts. Watch the lines’ flight.

Keep it kicking, pedal harder, find your balance, no use worryin’

Australiana gotta be there, trick the eye-bro. A cliché think-knot.

Think.

Not.

What do you want then? birds on wires?!

Poke fun at shay-dee PeeDes-Treeans? They fight back, you know?

no?

![]()

CERBERUS

DARREN PICKETT

I moved to point something out on the horizon, but Pop raised his tender claw to restrain me, his bulbous knuckles wrapped in cellophane.

‘Don’t point! You’ll put a hole in the air.’

I smiled. He didn’t. He looked at me behind steam piping from his teacup, juggling his dentures. He motioned at the sun rising. The arc of his gesture cradled the breadth of our view and took it in like a choirmaster drawing the voices of angels to a close. He shut his eyes.

‘An endless vista of terracotta trapezia.’

He opened them again. ‘Go to the centre! See for yourself how they have stripped the paint from the dome of the sky! How they have stapled their flags to the clouds! See where they have put holes in the air! See for yourself!’, he said, with spittle.

So, I fled for the interior, leaving the rind of the watermelon for the flesh of the country, where I thought I’d glisten my cheeks with the sweet wet of it and gleefully spit out the pips.

I bought a ticket that morning and boarded an empty train. I managed to catch a glimpse of Sydney’s skyline, with its stupid champagne bucket at the centre of it, and all the sprawl agroof in supplication. I was excited: I was going in the right direction.

It was a long trip. The dining car man was the only person I saw. He took cash for my pies with a tender claw of his own.

I arrived at the end of the line, in the flesh of the country. My hoodie was good for nothing but a useless sun visor. The glint was unbearable, and it took time to adjust from the dark of the train. The dining car man stood at the end of the platform looking down at the earth, shielding his eyes from the overwhelming sunshine, motionless and observant.

With some time to adjust I saw the dome of the sky Pop was talking about, not yet stripped, but certainly punctured. And no flags stapled to clouds, but shade cloth strung to bear some of the brunt of the pure sun that bore upon the ground and scorched all in its wake. What were they thinking? It was like going to the beach and erecting a postage stamp as a beach umbrella.

A building, torched, stood defiantly, only the refractory brick survived. Inside, I spied a bucket melted into the gravel.

The laser like beams of sunlight traced their arcs in parallel upon the ground making beautiful patterns of charcoal where they despatched something they could burn, or obsidian where they could not. The patterns were sundials I couldn’t decipher, but the trend was clear enough: we were all about to run out of stamps.

I hurried back to the station. The train was gone, and the dining car man had been replaced by a three-headed kangaroo welcoming me to the expanding threshold of hell.

![]()

UN SETTLING

JO CURTAIN

It is un settling

she is starting to take an interest

murmuring,

dreaming eyes

flickering,

rolling,

stop

she is walking,

finding her way

to something

other than

what she has

on dust-beaten roads

leading west

someplace else

under a polka-dot sky

watching

a mob of kangaroos

performing she

is turning

and turning

and as it is nearing summer

she talks

about the weather

and the

price of fuel.

![]()

PHASCOLARCTIDAE

GEOFFREY GASKILL

The picture on the wall stared down on them.

Sybilla asked the question for all. ‘What does it mean?’

Such small talk replaced hysterical screaming after the elevator juddered to an abrupt halt between floors. It was Lai who squealed first. ‘How are we going to get out of here?’

They might have pressed the Emergency button but even the disembodied voice assuring them help was on its way didn’t calm their nerves. It would only take an idle word to shatter their eye-flicking silence.

Lai and Parris were grateful to follow Sybilla’s pointing finger to look at the framed picture on the wall rather than think of their predicament.

‘Whatever it is,’ Lai said. ‘It’s not to my taste.’

‘I’ve got to say it’s not the most calming thing to look at when you’re stuck …’ Parris caught herself. Why refocus on their situation? Instead, she declared it, ‘Outdoorsy.’

The others nodded.

‘That’s good. Isn’t it?’ she asked looking at the other two.

Sybilla changed the subject when she waved a nervous finger and asked, ‘Why, do pictures about Australia always have to have kangaroos in them?’

‘Or cockatoos,’ said Parris.

‘And koalas,’ added Lai, who’d spent much of her life in Asia. ‘But kangaroos are kind of cute.’

Sybilla and Parris looked at each other. Sybilla cleared her throat. ‘They can be as vicious as rottweilers,’ she said, glad to talk of other things than a stuck elevator.

Parris nodded. ‘It’s a popular misconception,’ she said. ‘You wouldn’t catch me near one.’

Sybilla said, ‘Koalas aren’t cute either. They lose their charm after they’ve pissed all over you.’ At least that made her giggle. Her laughter was infectious and lightened the mood.

‘Wait till you hold one when it gets an erection,’ Parris said.

‘Like men,’ Sybilla added. She and Parris hooted.

‘My boyfriend was like that,’ Lai looked embarrassed but, in a show of sisterly solidarity burst into laughter too.

They all looked at the picture again. ‘Kangaroos,’ Sybilla said.

‘Koalas,’ added Parris, laughing.

‘Pissing and erections,’ Lai chortled loudest.

Being stuck in an elevator couldn’t kill the laughter.

Just then the doors squeaked before opening enough for a man to poke his bearded face inside. He was big and grinning and round-faced. ‘Hello ladies,’ he said, ‘sorry to have taken so long.’

As the three women looked at the man’s features, Sybilla roared, Koala!’

That set the others off.

‘What’s that?’ Parris said trying to control herself. She pointed to a badge on the man’s overalls. ‘Oh no!’ she howled, relapsing into hysterics.

On his breast the man’s logo identified him as being from Koala Maintenance Services.

‘Koala!’ screamed Lai, joining the other two.

‘No,’ the man told them. ‘Dick.’ He extended a hand. ‘Let me help you.’

‘Not likely,’ Sybilla told him as the other two women roared in helpless laughter.

Dick frowned, looking from one to the others. ‘What so funny?’

![]()

a country road near you

john heritage

![]()

THE TRUTH SHE HAD LONG KNOWN

CATHERINE BELL

It’s a shocking sight: a row of prams abandoned in the sub-Arctic cold.

As the woman draws closer, powdery snowflakes begin to fall. The prams turn ghostly white, coated like a thick dusting of icing sugar on cupcakes. They become almost indistinguishable in the quiet city street.

She peeks into the prams. Each one holds a small bundle. Her instinct is to rescue the sleeping babies. But they are cocooned in layers of warm clothes like tiny, well-wrapped parcels, oblivious to the extreme weather.

Peering into the café window, she sees several young women seated by the window cradling cups of hot coffee.

She shoulders the heavy café door open and squeezes inside. The place is buzzing with ruddy-faced, fair-haired, thickly set Viking stock. The guttural sounds of old Norse fill the air.

It’s her first day here and the foreignness of this country hits her. She feels different. An outsider. Doubts about intuiting a sixth sense, a connection to this land, play with her mind.

An elderly man dressed in tweeds, offers her a seat and inquires:

Why have you come to Reykjavik?

She wants to tell him she’s Icelandic too.

Instead, the woman replies:

I’ve always wanted to visit. I’ve read every book about Iceland in my local library.

Over the next few days, as large pillowy, volcanic ash clouds plume high over Reykjavik, she explores its galleries, museums, cathedral and harbour. Gale-force Icelandic winds buffet and toss her like a ragdoll along the streets.

Everything is unfamiliar. The language, customs, food, the people and especially the extreme cold. There is no sign, however small, confirming what is deep within her soul, a connection to this remote island in the North Atlantic Ocean.

The following week, on her last day in Iceland, the woman visits the geothermal hot springs in the countryside near Flúdir. It’s quiet, few people are here today. Instead, she is surrounded by nature: Iceland’s grass and rocks, sky and wind.

She slips into the healing waters, soft and warm on her skin.

Ribbons of transparent steam rise from the outdoor pool, its swirling and dancing resemble the lightness and flight of ballerinas.

She floats, trancelike. Body and mind relax and drift.

A feeling of déjavu slowly creeps over her. The sensation is fleeting, just out of reach, like attempting to capture the gossamer threads of a dream. Gone before she can make sense of it.

It leaves her with a feeling of deep peace.

The woman is still questioning her feelings of connection to a foreign land when she returns to Australia. With the need for tangible proof, she applies for a DNA kit.

She discovers her DNA points to Scotland, Ireland, England and France.

Then she turns the page.

There are the words: traces of DNA compatible with Icelandic people.

Her stomach flips with quiet joy.

I am Icelandic!

Her heart was right. Her instinct was right. The truth she had long known.

![]()

THE YELLOW DIRT ROAD

DAVID BRIDGE

Awakening to the 60s,

Dorothy, sans Toto, poor pup,

Dons her mental anorak,

Securely zips it up.

From her pocket, something special,

Yet I will not tell a tale,

Suffice to say she’s on her way

And really did inhale.

Back to the Land of Oz now,

Looking different to before,

The yellow road is paved with dirt,

Her mind asks, ‘What’s the score?’

Three giant birds squark loudly,

But answer give they none,

For floating in the atmosphere

Are globules like the sun.

“Have you been through our quarantine?”

Enquire some nearby Roos,

“If you’re an anti-vaxxer, then we do not share your views!”

By now the heat has risen,

And her delusions fed,

Dot struggles up the roadway,

Where there’s a shade sail overhead.

Confused about her situation,

She scrawls, but in imagination,

Across the scenery, some frantic annotation.

Just then, and in the nick of time,

For Dot is all but dead,

A truck draws up full loaded,

With bricks to mend a shed.

The driver shouts, “I’ve found her, the sheila on the news.

If you ask me, she’s on something, or p ’raps it’s just the booze.”

“Whatever,” says his partner, “but we’ll need the ambos quick.

She’s looking really peaky. I’d say she’s awful sick.”

Now Dorothy’s recovering,

Although the path’s been rough.

She’ll warn you if you ask her,

“Be careful what you puff.”

The nurses keep an eye on her,

For what she says they can’t rely on,

Especially with those visitors,

Tin Man, Scarecrow, Lion.

![]()

SUBURBAN SCREAMING

MICHAEL CAINS

Matt only tolerated Peter – didn’t like him much. A smartarse who’d only lived in Bonnybrook for ten years. Matt was born there over seventy years ago. He had a wife once, but she’d left when their once profitable little farm began to fold in on itself. He’d turned it into a market garden, but that was harder work and she was having none of it.

City smog was visible on the horizon and suburbs slowly crept closer. Bitumen roads appeared first as the harbingers of progress, then poles and buzzing wires, then huge signs advertising cheap land and country lifestyle. The kangaroos acted quickly, moving elsewhere for uninterrupted grazing. A few cockatoos still squawked indignation at shiny, zippy little hatchbacks replacing lumbering old utes. The corner shop was now a supermarket with a carpark and lines showing where you couldn’t park. Strange hooded, grunting teenage creatures started to hang around. A school was being built soon.

Peter leaned on a post and they talked – first time in weeks.

‘Bit of rain wouldn’t hurt,’ he advanced. ‘Keeps going around us.’

‘Done that for a while. People scare it off.’ Matt scratched thinning hair. ‘They upset the weather patterns.’

‘I’m not arguing there mate.’

Matt grunted. Both market gardens drew from the same dam now the creek had dried up. Peter’s ‘special’ crop away from the road needed more water than veggies, and Matt knew he was struggling. Buzzing flies filled the holes in their conversation. These days they had more to talk about but didn’t know how to say it.

‘Your missus still around?’ Matt eventually forced himself to ask.

‘Nah. Ran off with me best mate.’

Another grunt. A lone cocky flew overhead, searching for a gang of hundreds that once lived around here.

‘Gonna take their offer?’ Peter looked down at Matt. Last time he had mentioned it Matt had snorted derisively. This time he sighed heavily.

‘Dunno. Nowhere near what I thought it would fetch.’

Peter didn’t reply straight away. He had learned that you never hurried Matt who today had said more than he usually did.

‘Developers make all the money, mate. Not us.’

Matt nodded, sighing again.

‘Can’t afford next years rates so I’ll have to sell I suppose. Thought I’d have a few more years.’

‘Me too, I guess. That last crop was half the size. New copper is nosey too.’

Matt had long guessed there was an ‘arrangement’ with the previous policeman for a blind eye turned. Matt suspected it was why the new car suddenly appeared in Big Ronnie Jackson’s driveway before he retired.

‘I drove round that new estate. People move in the day after the builders clean up. Roofs nearly touchin’. Not a bloody tree to be seen.’ Matt got quite breathless.

‘Yeah, there’s that. Seen the surveyors’ posts at the end of our road? Be bitumen here next year.’ Peter pointing at their dirt road.

‘Bloody progress!’

‘Yah reckon?’

Another cocky flew high overhead screaming laughter down at them.

![]()

A TRIP TO PARADISE

CLAUDIA COLLINS

I take the window seat and drape my suit over the aisle seat so no stranger can sit next to me. The bus eats the miles and I stare out the window—dirt road, some kangaroos, cockatoos perched on lampposts, a derelict shack. I close my eyes and think of Amy. Whatever possessed her to want to get married in Paradise? Neither of us has been back there in years.

*

I have always loved Amy. She was my best friend from the first day of primary school but lately my feelings toward her have changed. I daydream about her and have become tongue-tied in her presence.

At the Graduation Dance the girls sit together on benches down one side of the hall while they wait for the dancing to start. I want to ask Amy to dance but I am paralysed with shyness. My brother joins me where I stand by the door and we watch as Amy waltzes with Jordan.

‘You need some Dutch Courage, Max,’ my brother grins. I don’t like beer but I keep drinking, putting off that moment when I ask Amy to dance. My head begins to spin. I am outside spewing into some bushes when I hear a girl run past, crying.

‘That’s Amy. What’s up with her?’ My brother asks.

She must have seen me. How will I ever face her again?

*

The bus hits a pot hole, jarring my neck and waking me. I rub my eyes and stretch. Outside the window I see brightly painted billboards advertising the attractions of Paradise—the Golf Club, the Paradise Hotel, water skiing at Lake Paradise.

I check my watch. I don’t want to be late and I’ll need time to freshen up. Amy will be getting ready at her father’s by now. Her bridesmaids will be there fussing over her dress. They’ll probably laughing and drinking champagne.

Her father will have been dreading this day, dreading giving her away into another man’s care. He’ll drive Amy and her bridesmaids to the church. The car will have been polished to within an inch of its life. He’ll open the back door and the girls will climb in taking care not to crush the bridal gown.

I’ll be waiting in the churchyard. Brides are always late. Will she be having second thoughts?

Inside the church I’ll turn to watch her walk up the aisle on her father’s arm, her veil covering her face. The vows will be said. Will she be nervous?

At the reception we will dance. I won’t blow it this time, I’ve had lessons. I’ll hold her and she’ll nestle into my shoulder. I’ll tell her how much I love her, how much I’ve always loved her.

No! I can’t do that. I love Amy far too much to spoil it for her. Yeah, she is getting married, but she isn’t going to marry me … and Paradise? What a laugh! They should re-name the place Purgatory.

![]()

Leave a Reply