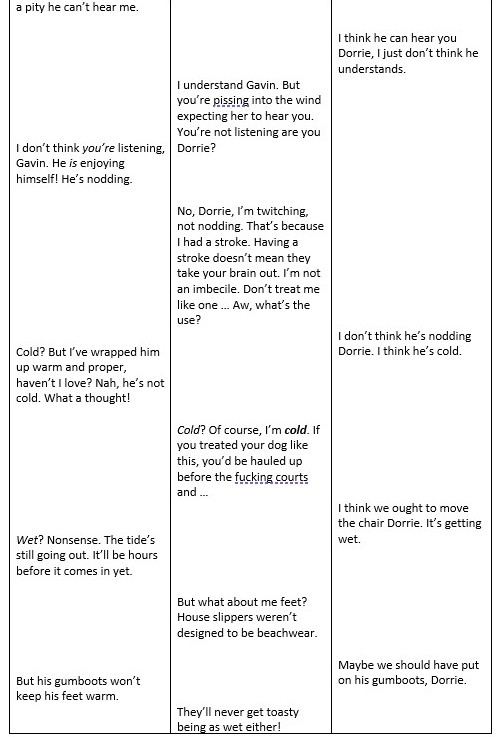

Thoughtful, by Jan Price

![]()

I DO SO LOVE THE SEASIDE

GUENTER SAHR

I do so love the seaside. I love it best in winter, when softly falling rain seduces waves to rest. A trusty chair, stout hat, a rain umbrella, my wellies and my mac are all I need. No. There’s more of course; I’ll take my thermos of sweet black tea and from its little mug I’ll toast the sea. Sometimes I’ll take my flute and at the early flood tide play Canute.

It is calm enough today to coax flotsam to landfall on the flood and bring words of love in corked bottles to desolate men. Morsels of love.

Ten years had passed since she wrote her scented notes and cast them out to sea in nineteen bottles to be taken by the Southern Ocean’s circumpolar stream. Messages in bottles. Messages in bottles. Sent out upon her passionate quest one morsel had come precariously to rest on the Islas Malvinas bringing light to a grey soul herding sheep on a wind-swept island.

![]()

WAITING

S.D. HINTON

When I saw my grandmother sitting on an old bentwood chair at the shoreline that day, I knew she was waiting. And I knew for whom she waited.

It started about six months earlier, when she began talking about the past as though it was the present and calling me by a name that although familiar, wasn’t mine.

Today she exists in another time and place, a place where life is simpler, happier, less ravaged. When she stands in her kitchen, her bent body appears straighter, and when she smiles, her lined face clearer.

‘Henry,’ she’ll say to me, ‘what have you caught for dinner?’

My name’s not Henry, it’s Zachary, Zac for short. And although I know the place she now lives isn’t real, I like that she thinks it is. I like seeing her happy again, hearing her honest laughter.

Happiness abandoned my grandmother on a squally day in 1976, when a man named Henry Short was steaming back to harbour with his day’s catch. Henry fished alone and was by all accounts a hard-working man of humble needs, resourceful and independent, often called brusque by those he didn’t care for. Henry was comfortable with his modest lot and adored his wife, as she did him. Henry was my grandfather.

I’ve heard the story of what happened to Henry that day in 1976 many times, and it still makes me ache for him.

Henry’s small fishing boat was old when he bought it, made of timber, and held together by layers of paint and glue and makeshift patches. By contrast, its engine was built to last, and Henry serviced and repaired that engine with the respect its lineage deserved.

‘The brass on that engine always gleamed,’ my father once said.

On that squally day in 1976, the sea was said to be angry and vengeful. The story goes that as Henry and his boat rounded a rocky headland, engine screaming, waves pounding the hull, spray lashing the small wheelhouse, a powerful current grabbed them, and they began to lose headway.

My grandmother said she knew there was something evil in the tossing air that day, and it was need that had sent her to the shore with her baby son to wait for Henry’s return.

‘It was so cold, and we waited so long,’ she’d say. ‘I didn’t want to leave the shore, but they made us you see, put their arms around me and took us home.’

I love my grandmother, her history, her character, her endurance, and as I placed my own bentwood chair alongside and took her hand, I gave thanks for one more day where we could wait together.

‘Think I’ll dig some spuds to have with our fish tonight,’ she said.

‘And there are lemons on the tree.’

![]()

silent thoughts

jo curtain

another wordless morning, I reflect

you desire nothing more than to sit

impassive

unreachable,

I reflect

on the smudge of shadow on the glassy, rippled surface

your breath competes with the squalling gulls,

bouncing,

infuriating

I reflect on the almost bitter taste the ocean delivers

you close your eyes to the startling white light blurring

horizon and water

until there is nothing left—

I need to believe that your silence will yield something.

![]()

D-DAY, AGAIN

JENNY HURLEY

There she is!

Linda’s eye follows Tommy’s index finger, pointing to a small black dot at the edge of the shoreline.

Looks like you were right, he says, it’s D-Day, again!

Oh Mum, Linda sighs, feeling both relief and dread as they start to walk in the direction of the tiny figure, seated in a chair at the water’s edge. Tommy has heard the stories many times before, but like a repeating, ubiquitous soundtrack, he hadn’t really paid much attention to his grandmother’s history, until now. It had been almost two weeks since his grandmother’s last disappearance. No longer able to live alone, she had come to stay with him and his mother several months back. He liked having her around, but he was beginning to understand why his mother was so worried.

How old was Granny when she came to Australia?

She must’ve been about 11 or 12 … it was just after the war finished.

And why did they leave England?

Well Portsmouth was devastated by the bombing, and for ten pounds they could emigrate. Before the war her father was a fisherman … that’s what attracted them to Portarlington … to the fishing industry here…

As they get closer, two parallel lines in the sand become visible, extending from where Joan is sitting, all the way up to the beach café.

She’s swiped a chair from the café again, Linda says. And looks like an umbrella, too.

Tommy shakes his head, a melancholic grin forming.

Mum, Linda says softly. What are you doing down here?

Joan turns her head, a vague sense of recognition on her face. Well, I suppose the cat’s out of the bag already…it’s D-Day… we’re not supposed to know about it, but I’ve heard Mother and Father talking about it, about all the troops secretly hidden in the nearby woods. We might be able to see something … I don’t know where everyone else is though…

Linda gently places her hand on her mother’s shoulder. That was a long time ago, Mum, in 1944, in England. You’re in Portarlington … in Australia now. Bewilderment fills Joan’s eyes, and her mouth opens and closes, fish-like, as she searches for words and memories.

Well of course, that’s right, we came to Australia … it’s just a … a … a commemoration, isn’t it? I heard about it on the wireless…

Come on, Mum, let’s take the chair and brolly back to the café. It’s time for breakfast.

![]()

THOUGHTFUL

DIANE KOLOMEITZ

Snug in my shelter near the ocean’s flow,

I watch the sea birds in their natural course

Of raindrop air, and water far below,

And ponder on my weather blocker’s source.

Unlike the birds, our skins do not repel

These skidding orbs, with oily feathers preened,

Or like the lotus, surface coated cells,

Stomata keeping leaf and bud pristine.

Lu Ban, a man and yet a water god

In Chinese legend, grew to certain fame –

When his wife, well-known for thoughts quite odd,

Considered tying lotus to a frame.

Such simplicity of leaves at toil

To keep her husband dry when clouds on high

Delivered soaking bursts to gasping soil –

Under his strange device, Lu Ban was dry.

Impervious to sudden change of clime,

Invention ended in a vast array

Of shelter domes for people throughout time –

Umbrellas gay on days of endless grey.

And now, I am content to watch beneath

Its sheltering arms on rainy days like these,

While breathing forms a thankful, misty wreath,

I’m celebrating doing as I please.

![]()

THE KEENING

CATHERINE BELL

It took four long years before I could start grieving for my mother.

When she passed away, I didn’t allow myself to feel any emotion. Losing one parent, then another, was too much to bear. Afraid of plummeting into a dark world of grief again, I placed a band of steel around my heart.

And as time went on, the memories of my mother slipped further and further away from me.

Eventually, I was unable to recall her countenance. She became a mere shadow in my mind, quite alone, looking out to sea.

Occasionally, I heard my mother’s voice. A voice both soft and haunting, reciting Tennyson:

Sunset and evening star,

And one clear call for me!

And may there be no moaning at the bar,

When I put out to sea.

The words were soothing and reassuring. I knew she was with me.

But still, I could not recall her face.

Until one summer’s evening far away from home, across the other side of the world, in Cambridge England.

There is a small congregation for the choral evensong service at King’s College Chapel.

I take my seat in the stalls, and gaze at the splendour. The brilliance is so ethereal it’s easy to feel a lightness of being.

Soaring fluted columns and arches; a deceptively delicate vaulted stone ceiling; medieval stained-glass windows rich in colour and detail; tessellated black and white tiled floor.

Organ music breaks the silence. Surging, swelling, swirling, filling every part of the Chapel with its energy. Then just as quickly, falling away, only to swell again. Massed voices of King’s College Choir rise above the organ as the Magnificat resounds throughout the Chapel.

Transfixed by the sheer beauty of the music, my prayer book remains closed on my lap.

Then memories of a mother, a loving ever-present mother, come flooding back. As I recall her gift for singing, her fine soprano voice, I’m brought to the brink of deep sadness.

The tears held back tightly for four long years arrive without warning. Muffled weeping is overtaken by loud heaving. My whole body is wracked with grief. I’m thrown into a sea of pain, unable to stem the torrent of emotions unleashed by music and place.

I cry the tears of a lost daughter, for a lost mother.

The organ music surges again and provides some cover for my keening. As I become aware of others’ concern, I slip away from the Chapel and find the grassy riverbanks of the Cam.

I sit quietly in the solitude, and close my eyes, exhausted, emotions spent.

My heartbeat slows. A calmness washes over me.

I open my heart to my mother.

I sense her presence.

She turns towards me and smiles. Her face is full of love for me.

I blink. She varnishes.

I feel deep peace at last.

![]()

THINKING ALONE

MICHAEL CAINS

Sitting by the sea and staring at life.

Restless flotsam drifts past my heart.

I should be searching, looking, feeling,

but I’m not seeing, I’m not thinking.

Just sitting.

Cries of gulls litter my ears.

Bobbing boats nudge grey water, patiently

anchored, but drifting like my mind,

under a stolen umbrella,

hiding from a rain-threatening sky.

Decisions beckon unbidden,

blankness competes with inaction,

but inertia wins.

Waiting, watching,

alone with a heaving sea

sucking out my bitter thoughts.

Soaking, not washing them away.

Horizon is too far,

tomorrow is even further.

Life surges

with tides of fathomless questions.

Don’t know what my thoughts say to the ocean,

know even less what they are saying to me.

Alone on wet sand, contemplating,

wishing, hoping, regretting, despairing.

(Need to move soon –

life and tides don’t wait).

The sea

wet, like tears

endless tears, endless wetness

shares my lonely thoughts.

![]()

SEARCHING

JULIE RYSDALE

Her little red plastic sandals left paw prints in the sand. Secretive animals followed her always stepping where she strode, slyly leaving tiny neat prints. Quickly darting on Barry’s coarse Welsh sand, she watched them follow and smiled her quiet smile. Turning, she felt the brief sun teasing the chilling breeze to see who would win. A tussle for sure. A day at Barry Beach.

With tidy elegance she clambered the craggy rocks, pausing, enthralled by the swirls and rivulets sculpting the sand beneath. Jar in hand she waited for tiny spiny crabs to scuttle and flee.

But too quick! she shepherded one into its new home and she named it. And loved it from that moment on.

Soothing her crabby friend, she scurried along the bejewelled sand tossed with mermaids’ hair, as the tide quickened its pace. Rocks disappearing to play their own secret games beneath a wild, purposeful sea.

The tussle was over, the sun painted her pale arms the colour of roses. She wished for shadows and shade, but her parents charmed her with cones of cockles on the bright pier. Briny and buttery. The taste of that summer.

But, oh no! She forgot. Her scarf! Her beautiful, proud scarf of sapphire and ruby and the gold of the sun, her glorious peacock charade. She looked, there it had been! Left behind, waiting alone on the rocks.

‘It’ll be gone now. Lost. China, most likely,’ they said.

A pause, so sad. Maybe, just maybe if she peered, she could see its joyful flourishing from the waves. Not drowning, but farewelling and voyaging, seeking freedom, autonomous and brave. With envy she turned and wished it safe travels.

…

Many years passed and she sometimes thought of her proud scarf lost to the sea: celebrating life with swordfishes and whales, delving deep into mountainous valleys, caverns of garlanded creatures of hues yet unknown, who summoned it on. She saw it beckon the moon over monstrous seas and dance a jig in the silver spotlight, chortling as it played with sleek dolphins and sang in tune with fair mermaids. She wished for its sass and reckless ease.

She too had journeyed, far from Barry. She had longed to chortle loudly, weaving swashbuckling yarns of ice cream days of childish sandcastles; tales of coloured beach umbrellas and reckless diving from giddying summits; stories of family and migrants in slater-beetle homes, strange languages and laughter and chasey and scorching summers of shared comic books.

But, a fringe dweller amongst her rollicking peers, she stayed in the shadows and held her heart close …

…

Barry was different now, yet memories remained. No cockles today. The mizzle matched the drab of her coat, her faded hair tangled with the wind, but safe amongst the oddness, she watched and held tight her self of long ago. A little girl with her friend the crab.

And she searched to find threads of sapphire and ruby and the gold of the sun, twined with strands of mermaids’ hair. Then she would know she was found.

![]()

THOUGHTS

ADRIAN BROOKES

Dawn. That day again. Butterflies swarm, a cup of tea to settle them.

Unwrap the heart. Call forth the ghosts from their mists of eternity. See their shades fill out and come alight with the bulks of ruddy flesh that once were so softly, shiningly warm. Reabsorb the sounds and smells, the quirks and foibles, all the cherished imperfections that fashioned those five human worlds: husband, brother, son, nephew and Cochyn the butcher’s lad, who in sharing the same fate became as much family as they.

Here they all are again, aglow in memory—almost, almost as they once glowed in her presence. Wrap them in all the love you have, for memories live only as long as those who remember, and the day approaches when remembering, too, must cease.

Walk with them down to the quayside as first light greys Liverpool Bay. She needs to stop and rest on the way now, so it’s not quite as it was then. But the boat’s all fitted and victualled, readied for cast-off. They board her, convert at once to crew. Cut the blether, too busy. No point in her hanging around.

She waves and goodbyes. Last words.

Lugs her chair to the beach. Thermos, hot tea, magazine, knitting, same ritual as every fourth of March.

And look! There they go, out of harbour in the spreading light, crashing through breakers and into the swell. Cochyn spares a sec to wave and grabs the rail to steady himself. Concentrate, Cochyn, boyo! The others are immersed already in course and tackle and nets.

Through a steam of hot tea she sees the ghost ship heave horizon-wards and vanish in the vastness of eternity.

Gone. Again. As on every fourth of March. The warmth of those five human worlds… Butterflies swarm again but she’s drunk all the tea. Bites a digestive and eyes the unstitched knitting, unopened magazine. Props. She only takes them because she took them on that day, which made them immortally sacred. Or for as long as memory remembers.

Her eyes are going to sting. She blinks the whole teary business away. Decided years ago she was done with it. They never made her cry when they were here, except the kind of crying she got from red faces, shiny eyes, wide grins, full bellies—oh, the roomful of noise!—erupting in Dafydd Iwan’s anthem ‘Yma o Hyd’.

‘We’re Still Here’.

Oh, dear. She wipes her cheeks.

Perhaps next fourth of March she won’t come. She folds the chair, plods back across the beach. And here’s the plaque with the crosses next to their names. She sighs, slumps onto the wooden bench. Lips move silently, reading the words; eyes blur and rise to the horizon. Perhaps next fourth of March she won’t have to remember any more.

![]()

SHE SAT

QUINLIVAN

she sat

in reflection

watching seagulls

and ships

pass by

undisturbed

contemplative

peaceful

blue skies

wonderfully calm

water still

she sat

![]()

WAITING FOR ROGER

JUDY RANKIN

The dog took off! Running free along the damp sand, stopping only to bark at the waves. If the waves weren’t too high, he’d jump at them as they broke on the shore line; followed by sneezing and coughing as the salt water went up his nose. Then he’d run away spluttering at the waves.

‘Roger!’ The Man called. ‘Roger! Heel. Heel!’

It was futile. While Roger embraced the freedom of the wide open shoreline, filled with excitement to the point where he couldn’t help but run, the wind threw the man’s voice away. So, The Man would meander along the beach using his umbrella as a walking stick until he caught up with an exhausted Roger who lay panting on the sand. When The Man got closer, Roger would wag his tail and walk quietly to heel at his feet.

‘You’re a naughty boy,’ The Man would scold. ‘One of these days…’ No one ever heard what would happen ‘one of these days’ as the man mumbled to the dog.

Each morning was the same. Other regulars on the beach would smile as they watched the pair go through their daily routine.

Once reunited, the pair would walk slowly back toward The Man’s car. Roger would greet anyone who came close enough to be sniffed, wagging his tail and stealing a lick. No one seemed to mind, except The Man.

‘Roger, don’t… Oh what am I going to do with you?’

‘He’s okay,’ the accosted walker would say.

‘No. He’s been told …’

The Man would frown at Roger who always looked pleased with himself.

…

One day, the regulars realised Roger and The Man had disappeared. All wondered why. Some worried The Man was ill. Others speculated that Roger had become too much for The Man.

After some time, The Man returned. Instead of walking the beach with his umbrella as a walking stick, he arrived with an old, tartan folding chair. Walking towards the water’s edge, he sat on his chair with his umbrella open above his head.

The Man didn’t walk. Roger was nowhere to be seen. And the regulars were full of curiosity. So much so, that one day a regular approached The Man.

‘Hey…no Roger?’

‘Not yet,’ The Man replied.

‘Are you expecting him?’ the regular asked.

‘I don’t know.’

‘Where – where is he?’

‘He ran away,’ The Man replied with a hint of sadness in his voice.

‘Oh, I’m sorry,’ said the regular. ‘Here? At the beach?’

‘Yes,’ replied The Man. ‘We came for a walk, he ran off – as he does – and I haven’t seen him since.’

‘Oh!’

‘I told him. ‘One of these days’, I’d say to him. ‘One of these days the waves are going to drag you in and you won’t have me to get you out’.’

‘Is that what happened?’ The regular asked.

‘I don’t know.’ The Man’s voice cracked. ‘I thought maybe if I sit here and wait, Roger would see my umbrella and come back. But, who knows. Stupid dog. I told him.’

‘I’m sorry,’ the regular said feeling truly sorry for The Man, ‘I’ll keep my eyes open for him.’

‘Thank you.’

The Man turned to scour the beach and the horizon as the regular moved on to talk to other regulars.

![]()

ETHEL AND FRED

ALLAN BARDEN

Every year on the same day, at the same time, on the same spot, on the sands of Everett’s Beach, Ethel sits and remembers. She loves looking out to sea observing the rolling tide, the waves, the seabirds. Rain, hail or shine it has become standard practice; a ritual for her since Fred passed away.

It was here, on this spot, on the beach, that she had dispersed his ashes five years ago.

Fred loved walking along Everett’s Beach, barefoot mostly so he could feel the sand and sea between his toes. Once it had been an occasional fishing spot for him until he decided that he could no longer kill fish; or anything else for that matter. After his retirement it became his preferred place to set up his easels and paints several days a week. Over the years Fred must have painted dozens of scenes from this spot, of waves, sunrise and sunsets, birds, boats, surfers and seashells. Most of Fred’s paintings had resided in his small studio at the back of their house, but when he passed Ethel had selected her favourites to hang in the house.

Ethel remembers fondly Fred’s fussiness at getting the colours of his scenes just right. He really was a pedantic man of colours. It was as if Fred kept his life in his paintbox. With closed eyes she can almost smell the scent of the oil and brushes interspersed with the smell of sea spray, seaweed and salt.

Ethel sits in Fred’s favoured studio chair which once a year she carries to the beach from their home which is close by. It helps her reflect and for just a short time each year Fred seems close. Thankfully it is not a long stroll for she realises the time will come when she will not be able to carry Fred’s chair to this spot any longer.

Fred loved colours but also flowers. Ethel has a bunch of red roses from their garden in the nest of her palm, thorns against her flesh as the tide tickles her toes. She remembers Fred’s ashes melding with the sea and the red roses floating away with the tide. She sees him clearly as if beckoning her.

Ethel hesitates and wonders if she should let the water and tide meander her a path down to the deeper water to Fred. She closes her eyes and imagines its cold slowly engulfing her legs, her arms, her chest until it had her all.

Ethel opens her eyes and accepts that Fred is gone. Even though she is alone, she knows Fred would want her to carry on and do what she does every year at this time, visiting him where he is not anymore. She arises from Fred’s chair, stands in the salt water and tosses the roses to Fred’s beckoning arms.

![]()

REFLECTIONS

JENNY FUNSTON

Reflections

Caught in the moment of torrential outpouring

Slithers and slides in glinting sunlight,

Held aloft

Memories unleashed

In studied serenity,

Claim the space,

Isolated yet connected,

Tide turns, life turns,

Boldly independent

Again

![]()

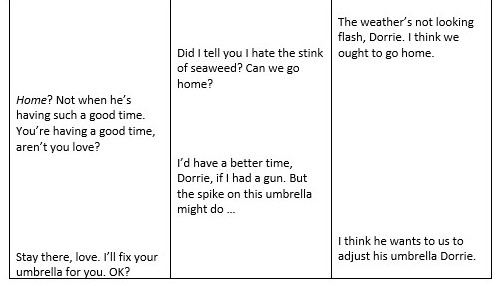

THOUGHTFUL THREAT

CORINNE SANDERS

Seagulls chirped on an endless loop. Waves crawled back and forth in a metronomic rhythm. The silhouette of a boat on the horizon was forever stationary like a ghost ship. The stark sky echoed into the abyss.

The vertical pencil line from the boat into the sky almost gave it away. The absence of footprints on the wet sand added to the evidence. If four meant death, then the birds exposed the truth.

The body slumped on the rickety chair. Anchored to the splintered wood was the murder weapon. Although, shielding her from rain or sun would be redundant. Dark blood dripped from the pointy end, staining the waterproof fabric. The hat concealed the stab wound.

Her lacy black dress and leather boots promised a funeral. No one was invited. Black roses on her lacy jacket substituted the flowers on her hypothetical grave. Her glassy eyes gazed out to sea through broken spectacles.

Dragging her to a real beach only to be washed away by the tide would have been pointless. The green screen maintained the illusion. The icy temperature in the freezer room delayed the stench of rotting flesh.

The portrait shot haunted a postcard. It flipped over to reveal the message: Greetings from paradise. I’ve been thinking of you.

![]()

A DAY AT THE BEACH

GEOFFREY GASKILL

Jan Price

Good morning to each and every writer who wrote in response to Exphrastic Challenge No 1.

I’m not even sure if I have the right to make comment on my photo contribution to this exercise.

After all, it’s about the photo – and therefore, objective, not subjective. But I printed them out

and read them all. It’s a strange sensation to enter each of your minds freely – yet not have been

personally invited. Your insights into ‘Thoughtful’ have traveled me to places my imagination might

never have visited as a poet. I smiled laughed and cried. You deserve to be thanked so I’m thanking

you and keeping you all in my good-memory trunk. Blessings – Jan Price

Jenny Hurley

Thanks, Jan. Of course you have the right to make comment! Thank you for printing and reading all of our responses to ‘Thoughtful’. I’m curious to know about your ideas behind and inspiration for the photo?

Michael

Thank you Jan, for your lovely comments. This was my first real try at an Ekphrastic piece, and it won’t be my last if I am excited by simple pictures like this one. Dipping my toes into the water, so as to speak. – Michael

Jan Price

Hi Jenny – lovely to meet you and your wonderful story!

Thank you for your question re ideas and inspiration.

My mother had an Irish sense of humour. She loved children,

Egypt, music, singing, (taught ballroom dancing in the Melbourne townhall).

She could sell her paintings to tourists and lie ‘Yes’ when asked if the painting

they were about to purchase was the only one of its kind. After the buyer left,

she would race up the steps of her caravan, pick up the same subject on canvas

down the steps again and place it on display for the next customer. She was a nurse

a seamstress and my father gave her hell. She gradually gave in and became

silent. I would find her sometimes sitting on a chair staring out a window

at sunset – as if the window-frame didn’t exist. She didn’t like wearing shoes

and her heels became cracked – so I thought seawater could complete the image.

She is now an occasional visitor in my dreams.

My explanation is long-winded but I wanted you to know her.

Blessings for your question Jenny – Jan

Jenny Hurley

Oh, Jan, that is such a wonderful, poignant story of your mother! Thank you so much for sharing it. And not long-winded at all … could be the start of a longer piece, perhaps?

Jan Price

Hi Michael

I hope you are still ‘there’ ?

Most sensitive poem – beautiful!

Blessings – Jan (Price)

Jo Curtain

Thank you, Jan, for sharing such a magical photo. I love it. Jo 🙂

Jan Price

Hi Jo

You poem is full of human understanding – such a gift!

I wish I could send you a couple of photos that you might

also consider to be ‘magical’ – you could write more poetry

like ‘Silent Thoughts’.

Thank you Jo